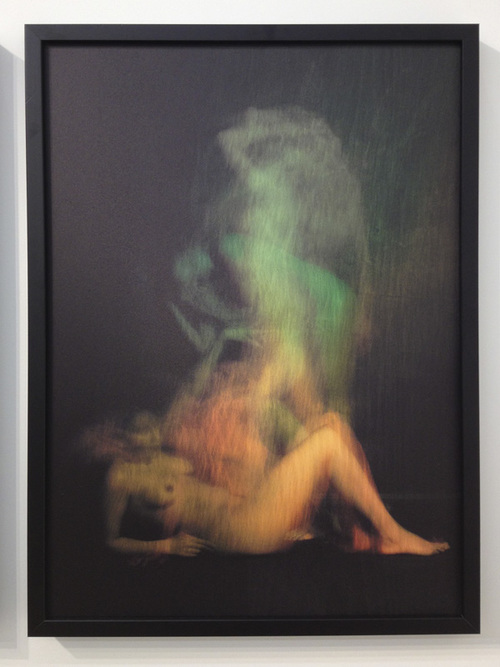

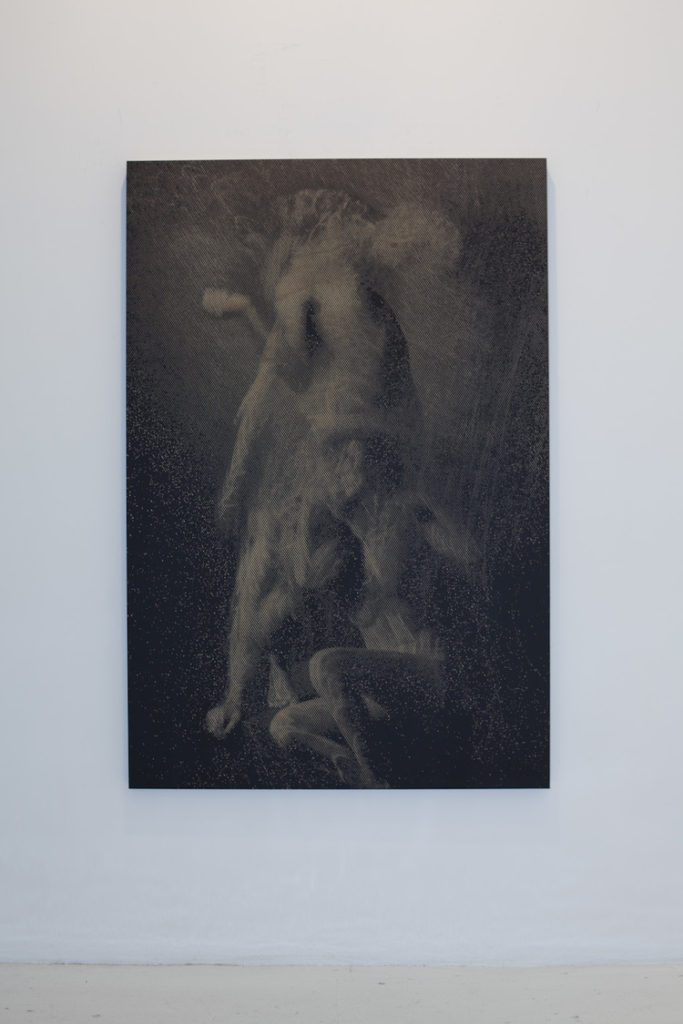

Matthew Stone is a London-based artist interested in contemporary shamanic practices. His work extends across photography, painting, sculpture, parties, and performance, and is characterized by collaboration and a preoccupation with the possibility of materially presenting the immaterial.

He was instrumental in shaping the art collective !WOWOW!, a community of artists, musicians, designers and performers squatting in South London, and has exhibited in solo and group exhibitions at the Tate Britain, the ICA, the Royal Academy of Art, the Marrakech Biennale, and the Fiorucci Foundation. He has also staged performances at the Ny Glyptotek, Copenhagen and at the 2013 and 2014 editions of Art Basel Miami Beach, as well as produced commercial photography for various publications and clients, including the album art for FKA Twigs’ recent EP M3LL155X.

We Skyped and talked about Kanye (omitted due to space unfortunately), squatting, optimism, and the problematics of iconography. We talked about a lot of other things too… This dude is crazy…

You can see more of his work on his website, blog, or Instagram.

Kenta Murakami <3

diga.rt: There is an immediacy to your photographs that reminds me of something like a Caravaggio painting or of Mapplethorpe’s X Portfolio. In some way I can see how critics might pan the work as overly indulgent or as lacking in content somehow – simply because of how beautiful they are? Yet for me, due to that formal immediacy, there’s a certain presence to the work that begins to feels really performative. Have you ever encountered any pushback against your embrace of such sensual imagery?

MS: I remember someone saying to me once, “The problem with these works is that they’re so beautiful.” This was a long time ago and I remember trying to justify that sense of traditional beauty, claiming that the aesthetic presentation of the works was purely a conceptual element, that it was part of a desire to debunk the philosophical possibility of objectivity that rejecting aesthetics is sometimes associated with.

I felt like some artists were co-opting Minimalism as an aesthetic because it seemed like the most un-aesthetic aesthetic, when actually that’s kind of ridiculous because it’s possibly the most successful aesthetic of all time. I mean if you look at Ikea, it’s sort of just Donald Judd sofas.

I feel like my feelings have changed a bit since that initial, visceral reaction. I remember for a long time worrying about, but still not being able to extract myself from my desire to think formally and to try and make things beautiful.

I feel less apologetic for it now. I completely understand why beauty is problematic, as it instantly implies hierarchy: if one thing is beautiful that must mean that something else must not be. But at the same time I also see that definitions of beauty are slippery. I feel like when artists have consciously tried to reject notions of beauty at large, essentially all they’ve done is reject one established notion of it. And in that moment they often create new aesthetics that in turn become new standards. So it is this mercurial thing that appears and disappears, and in the process of disappearing re-emerges and expands our definitions of beauty.

You can have a beautiful idea too. So the immaterial works that emerged from Conceptual art in the sixties, they can become beautiful in themselves.

diga.rt: Totally. I think the notion of eluding beauty in art can get a bit silly. When people look at art they’re looking for something beautiful to some extent. Baldessari’s conceptual photographs, for example, where he’s throwing these balls in the air and photographing them; even if they’re not composed in a strict sense, we still find them beautiful because there’s something fortuitous about them.

MS: Because we project.

diga.rt: Yeah. Projection is something that interests me in your work in the opposite direction actually. You have all of this beautiful work; then you have this other side that comes through in your interviews that’s really heady, yet I definitely feel like I’m able to feel both at all times.

MS: Well I hope so. I often find myself talking about ideas in an abstract sense rather than talking about my process. It’s not that I’m not prepared to think about my work, but I feel like I need to create room to be instinctive.

I’m not in the business of making literal illustrations of my ideas, whether they be visual or conceptual. I’m more interested in making something that is in the spirit of my ideas. I just feel like if I work in that way my work is going to be more honest. I think that there can be a danger in second-guessing the way that you are making something, and in second-guessing things out of existence before you have a chance to understand what they are.

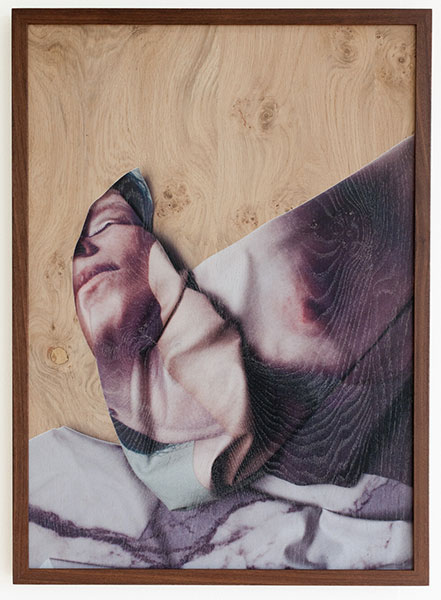

diga.rt: To go totally against that and to linger on the formal aspects of your work, I’m interested in what drew you into three dimensions in exhibiting your photographs….

MS: Well it was only really a matter of weeks before I graduated that I started using photography as a means to an end in creating works.

diga.rt: And you studied painting?

MS: Yeah. And in a way I feel like photography still somehow has this power of implying objectivity. I understand that philosophically that has been debunked a long time ago – that the way a photographer frames a picture has a huge impact on what a photograph says – but I feel like I spent a lot of time trying to prove how much is created or controlled in the moment of photography. Because I’ve been involved in a lot of performance I’ve always been interested in the idea of the camera as a sort of lightning-bolt conductor that creates a moment rather than simply records it in an unfiltered way.

And in a sense that’s really obvious in the way people use their phones now. People are motivated to do all these things so they can then put them on Instagram. But I am not trying to discuss that in a cynical or judgemental way – like in the sense that we’re disconnected from real or authentic experience – but in actually looking at how the camera can be seen as an intensifier of experience. How in a ritualistic sense it becomes a kind of shamanic tool that allows people to invoke a situation. And when I was shooting the group nudes, the studio did become a sacred, ritualized space. It was about setting aside a period of time that deviated from mundane life.

So I think I was trying to escape the gravity of photography. And I wanted to try to create a space where something was moving through dimensions. By creating something that is both two-dimensional and three-dimension it represents a moment that is just before something happens. It also has future potential in it. So a lot of the sculptural things I made were modular in the sense that they were either hinged or involved fabric. So there was a sense to the work that it had the potential to continue unfolding.

The works that I’ve made that involve other people are also highly collaborative, and they stem from a period of my life that was almost entirely collaborative. It was a period where I was squatting and organizing exhibitions, art parties, and residencies. Basically we were organizing spaces where people could make stuff.

I think it was also about implicating the audience.

At the time I was doing a lot of exhibitions where I would install photography and then do a performance, and then photograph the performances with the audience in it. So there was this layering of involvement. We were creating a space that focused on play in a sense.

I feel like everyone that came became quite involved. And not in a forced way, but just in the sense that it was a carnivalesque environment. I think I was really thinking about this idea of interconnection and collaboration and navigating conflict when hierarchies emerged. I was trying to be honest about that level of involvement.

diga.rt: The more of your work I see the more collaborators I realize I recognize… I mean Gareth Pugh[link no longer accessible], Twigs, boychild, Michele Lamy, Zebra Katz, Shayne Oliver (links are no longer available), Dev Hynes…. I’m sure it goes on and on and that’s only the faces I recognize…. Do you feel like there’s a generational tendency to some extent towards collaboration or community building?

MS: It’s funny how someone can say one thing to you and you’ll always remember it. In college I was making a lot of work that involved me as a central performer. I was designing performative tools, like suits with these esoteric symbols and sculpture designed for performance, and one of my tutors said to me: “We like your energy, but it’d be great to see some work that stands alone without you either being involved in it or having to explain it.” And it really struck a nerve. Or, I don’t know… I took it quite seriously.

I was like, what can my work be about if it’s not about me? Not that that’s an existential question or anything, but just as a literal response to her… (laughing) So I was like, if it’s not about me then maybe it’s about everyone around me?

So I started taking photographs of my friends. And that was just a couple of months before my degree show. And then after I graduated I started squatting.

We used to spend a lot of time making these crazy outfits to wear when we’d go out. And my friend who’s a fashion designer – Gareth Pugh – we’d make these group outfits that sort of interlinked. So it was a really playful, highly creative period of my life.

diga.rt: That gives a lot of context to Gareth Pugh.

MS: Yeah, oh totally. I mean his first show was in the nightclub Kashpoint, which was this underground, electroclash dress-up club. And it was interesting, it wasn’t in any way about looking good. Like I can’t imagine anyone we knew having sex in that period. (laughing)

But in terms of collaboration… It’s hard to list everybody. There was this period of creativity that was completely outside of anything – it was kind of its own world in a sense. We had taken over this 7000 sq ft building with four floors.

I remember this one time we’d been collecting stuff that we’d found on the street and the police stopped us and were like, “Come over here.” And I remember turning to my friend and being like, “Let’s just go,” and turning around and going through the front door and locking it. And the police left! It sort of symbolized how much we believed that the building was our own rogue state and that we had – to borrow a phrase – built this temporary autonomous zone.

And we weren’t just working together; we were our own audience as well. In hindsight it’s weird, but I feel like – I mean everyone had ambitions for their work – but there wasn’t this kind of hunger for traditional commercial success. We weren’t trying to get galleries or I don’t remember ever having conversations about the prices of someone’s work. People were making things that were mostly being destroyed with the buildings that we were occupying. And this was all pre-2008 crash, like 2004-2005, so it was a really weird time to be doing that. Like we should have been being cynical and making tons of money.

So yeah, there was that period of collaboration and then it sort of naturally came to a head. We were doing these parties that kept getting bigger and bigger. The last one was in this other alternative art space in South London called Area 10, and we did this week-long event that had like 2,000 people at the end in November and it was freezing. I think we realized that the next time we’d do it it’d just be a festival. So even though we’d tried to design it to be headless, it’d developed the potential to become a brand.

There was never really a discussion, but everyone just knew that that was the last party we’d do. And then we did something at Tate Britain.

diga.rt: So it was sort of a natural transition from one to the other?

MS: A lot of the creative relationships remained, but yeah, there was a shift. At the time I had been reading a lot of Joseph Beuys’ ideas on social sculpture and the idea of these multi-author works that were embedded in society rather than in a gallery space, so at the time I felt like when we were doing that stuff it would be diluted if it was put in a gallery context.

I thought people would see and understand that my work existed in a social realm alongside the material works I hung in galleries.

And it’s interesting, because in a way it bridged a cultural gap relating to the internet. Like the first parties we did we promoted on Myspace bulletins. And they were the first illegal parties – as I understand it – that were promoted online. There were squat parties in London of course, but you still had to phone the number on the night – and you had to know the number – in order to get in. And I think for that reason we went totally under the radar of the police.

I mean the police would eventually show up, but at that point there’d already be some 800 people inside, so they realized they couldn’t really shut it down. And someone told me that the worst thing a policeman can do, in terms of getting in trouble, is inciting a riot. So they’d say “Who’s running this?” and we’d be like, “Oh everyone”. And they’d be like, “Well, I think we’re gonna have to shut it down soon” and I’d be like, “Well everyone’s having a really good time, everyone’s really calm. But if we shut it down people might get angry. I would hate for you to incite a riot…” So I used a bit of manipulation and probably some white privilege to keep the party going.

But in a sense it wasn’t about rejecting the gallery system for what it was either, but simply that the work would’ve felt fake or like a parody of itself. The way that people would engage with it would undoubtedly be different.

We were navigating – and in some sense manipulating – the ways that emerging culture was being co-opted by brands and style press at the time. I think it felt like a lot of things in the past were underground because people rejected commercial success, but also that commercial success wasn’t so attainable.

Now as soon as something emerges brands want to identify with it. So the opportunity to fund projects is different.

diga.rt: It sort of brings up the idea of the avant-garde, in the sense that it’s less about one’s position within the market than one’s relationship to power.

MS: Sure. And you also have to be realistic about the fact that taking work into an institution creates a lot of validation for the work. Making a living for what you’re doing is a very fragile state.

I was having a conversation with Shayne (Oliver) from Hood by Air and he was saying that people often call him an underground designer. And he objects to that. He believes that the underground doesn’t exist anymore, and that there’re only emerging ideas. As I understood him, he thinks the idea of trying to maintain an underground status is an exercise of privilege because it’s only if you can afford to remain underground that you can choose to do so. There is a danger of fetishizing suffering as well. It’s a precarious situation trying to maintain autonomy while sustaining yourself and your ideas.

diga.rt: Your interest in shamanic practices is most evident in your performance work. In Anatomy of Immaterial Worlds, for example, you created a soundtrack that shifts from more traditionally structured music to repetitive, droning noise. You’ve stated that the intention is to create an experience of sensory deprivation, creating a head space in which the audience must then look inwards.

I think the notion of finding silence within noise is really interesting, as in a sense it seems to be the opposite of the Zen-influenced ideas of John Cage. For him, through silence the viewer is exposed to the aleatoric or the chance encounter. Instead, your work emphasizes the meaningless of noise so the viewer can disassociate from it, and is therefore allowed to start over with a renewed possibility for intentionality….

MS: Well because the drone sound is repetitive – it’s really loud and really bass-y – it blocks out all the tiny noises you can hear. I also present the piece in the dark, so you can’t really see much. But regardless there’s something about the structure of monotone music that’s hypnotic.

I think it has something to do with how music has a narrative sense to it. Like if you think about dance music, where something builds, and then it drops, and then it kicks back in… That feeling of pleasure when it does kick back in has to do with the fact that you were able to predict that it was going to come. You feel this sense of release that what you knew was going to happen has happened. And there’s a sense of safety in that, which sort of keeps us based in time.

But with truly monotonous music, when it starts you have an awareness of how long it’s been playing. But there comes a point where you can’t remember how long it has been playing, and you also can’t predict when it’s going to end. So my theory is that by losing a sense of time-based structure, the rigid structure itself sort of releases us from our sense of linear time and allows abstract thoughts to emerge.

I have similar experiences when watching a ballet or a really long opera. I think there’s a certain durational aspect to it too, where I come out of these time-based pieces that aren’t strictly narrative and I have all these ideas. And it’s not like, “Oh that gave me an idea ‘cause I saw them doing this;” it’s not inspiration in that sense, but it’s inspiration in a sort of mystic sense.

diga.rt: I totally get that. My school had this Phillip Glass festival, and when listening to him play my mind would get super distracted to the point that I’d realize I hadn’t even been listening for half a composition. It was like meditation.

MS: It’s a different way of listening. And the performance you’re referencing (Anatomy of Immaterial Worlds) was experimental in that sense. It was only really possible to understand what would happen with an audience in place. And it’s kind of the only thing I’ve done where I’ve received really varied feedback. Like insanely varied feedback.

What’s nice about it is that people feel completely confident to tell me that they hated it. Like, “that was a really horrible experience.” Which is great. And it’s great not only in a sense of like, “I wish everyone was that honest,” because you know, I have an ego, and if everyone was that honest all the time I’d probably be sad… But with this I really wasn’t. With this I had this desire to understand what was happening, what effect it had on people, how they’d react.

I also had some people who thought it was incredible. People telling me about having conversations with penguins or how it reminded them of meditation. There’re so many funny stories.

A guy wrote to me and said that he felt compelled to write because when the performance started he had this epiphany that what I was doing was like, the most intense form of bullshit he’d ever experienced; that I had sort of peaked on this cultural decadence. But then that it changed, and as he started to think about it, he started to think about the future and started to think about hope.

And I got the feeling that he didn’t know that I’m always going on about optimism. (laughing)

And he said that he felt like he was on a ship that was moving forward in time. And I’m not just telling you this cause it’s really complimentary, cause there were enough people that really, definitely thought it was bullshit – I mean every time I’ve done it at least a third of the audience has walked out – but that when it finished he said he was scared to leave the theatre cause he didn’t want to go “back to the past”.

(laughing)

It was really sweet.

So it does do something. I mean the patterns, in terms of the tempo and strict rhythm, are based on the monotonous shamanic drum patterns that I’ve researched or experienced. So I kind of knew that it’d work…

But anytime that I’ve met people that are doing shamanism it hasn’t been indigenous shamanism; it’s appropriated, filtered through a western lens. But it’s still committed to the local trappings of like using a deerskin drum. So I was interested in what happens if I use a software version of an analog synth, like, if I’m using a Korg MS20 in Ableton, does that mean that we get to talk to the spirit of Ableton instead of the spirit of a deer? Or is it just that it’ll still work.

diga.rt: And what were you trying to accomplish?

MS: I was interested in pushing people to a state where they are really far from where they are when they enter a gallery space and they take off their “I’m-going-to-look-at-art” thing, and go somewhere else. And I was interested in what traditional ideas of high culture looks like if we shift our brain state – ‘cause the way we look at things is so informed by the ways we’ve been taught to look at them – and if it’s possible to get back to a state that isn’t bound by that, that’s un-cynical in a sense.

diga.rt: To get to the big question…. In what ways do you see optimism as a form of rebellion? I ask because I find that so much of the art world is built around a critical distance that seems rooted in a kind of skepticism. The result is that so much of art being made today seems to require a certain amount of irony to get by… I find the sincerity of your work to be really rewarding.

I’m also asking because something that’s interested me recently on a personal level is this slip-up between the meaning of idealism and pessimism…. I guess what I mean is that me being idealistic means I have a certain faith in optimism, but that simultaneously I have a certain disenchantment with the present, or that I see that we’re not there yet… Optimism thus becomes a very active mindset rather than just another form of complacency.

MS: I wrote this manifesto in 2004 with a friend of mine called Brianna Toth, which is where the term came from, and at the time it really felt like it was culturally rebellious. People were talking about utopias in art, but there was the sense that it was hopeless; basically they were saying they’d go ahead and make the work they wanted to do, which was about utopias, but they’d talk about utopias because it was going to be obvious that they were being critical, or that they were pointing out that utopias have historically been linked to totalitarianism, or that idealism suggests a set of ideals that are always going to be oppressive in the end.

So, from that position I held this weekly salon where people would come and talk and we talked endlessly about optimism. So I feel like my ideas developed because I brainstormed with people. And I think it was an important thing for me to do because I was aware of why people feel like optimism, or more specifically idealism, is dangerous.

But something that came up early on is that it can’t just be blind optimism. It’s not this passive acceptance that everything is just going to be okay. Then later we came to this agreement that optimism has to acknowledge suffering, and so, in a sense, one definition of optimism is the triumph over suffering.

I mean people always talk about art in relation to suffering. There’re these figures that sort of stand out as demonstrably depressed, and people attach their creativity to that depression. But when you’re depressed you can’t really do anything…. So how were they doing stuff?

If you really look at those people, say if you look at how Louis Bourgeois talked about art being the only thing that kept her alive, then art is the thing that pulls people out of suffering.

And so maybe art needs suffering in the sense that art is the passage out of it? But I’ve argued that at its root all art is optimistic. That the act of making something rather than nothing is an optimistic stance; it projects towards the future. And it also points towards a faith in the potential for connection or communication.

So I’d just go back and forth in thinking that there’s so much going on in the world that makes this feel like decadence. But at the same time, it felt like the alternative to that was compliance.

And I understand that a lot of people use irony and nihilism as a way to attack bourgeois, stagnant systems of belief… But at the same time I watch it trickle down through culture and I watch it being taken at face value. And just from a practical perspective, I don’t think it’s achieving its end.

I think that idealism as a stance – that there are ideal version of things somewhere out there and that we should work towards them – is problematic. And – Well… I guess postmodernism has to be brought into this at some point.

(laughing)

I understand postmodernism as the death of singular truth, to boil it down. And I feel like – you know – the death of God was declared. But that a lot of the reaction to that was, and perhaps continues to be, a cultural mourning of grand narratives.

diga.rt: I think it’s interesting how progressivism as a political movement can feel like postmodernism regaining the reigns again in a way that can be problematic – or perhaps is problematic… Yet for me personally, I don’t understand the alternative….

MS: Well it’s not like postmodernism shouldn’t have happened; it’s just that people took it literally. They were like, “Okay, so God is dead… and there’s no truth”. But no, it’s like instead of one singular truth, we have crazy complicated truths that we have to keep constantly processing and see from different perspectives.

But, at certain points, we have to draw conclusions because things are actually happening in the world and we have to make decisions about how to react to them. So in a sense there’s a fluidity that emerges from postmodernism. And while the knee jerk reaction might be that it’s the death to all possibility, it’s actually just an enlarging of it.

I’ve stated before that optimism is the vital force that entangles itself with, and then shapes the future. So even if you’re not feeling optimistic, when you do anything consciously there is optimism inside of that action, and that is the thing that projects you forward into doing.

And of course that opens a million cans of worms. I’m not trying to say I have the answers, but just because ethics is complicated it doesn’t mean that nihilism is acceptable.

I guess what I’m arguing is that it’s possible to be idealistic without creating fixed ideologies. It’s about moving targets. It’s about constant discussion, about listening, and about processing that we exist at a point in history where we’re not only globalized, but insanely networked. And I feel like there’s a cognitive evolution going on where we are adjusting to globalization and in so many ways we’re still processing that.

diga.rt: I feel like we’re still lacking the vocabulary to talk about things like spirituality or morals without the trappings of language that now seems naive.

MS: Do you know the book Techgnosis by Eric Davis? He writes about technology and spirituality and how as we’ve developed information technology there has been a spiritual evolution that has coexisted and developed in response. But the language that he uses is lush. And some of it is quite, for want of a better word, lol-sy. Like at one point he ends a sentence with “reality bites,” only bites is spelt “bytes.” And what’s amazing is that the writing has this feeling that could veer into the verbose or florid, but what he’s saying is really solid. And it’s almost like while you’re reading about it you’re searching for his agenda – because when you read about this kind of stuff you’re like, this kind of person has to be anti- something or that there must be a golden age that we need to get back to. But it’s not there.

He has an intense interest in modern expressions of spirituality. Like he writes a lot about burning man or the first-wave internet artists that were techno-pagans with computers facing the four directions and stuff. It’s all kind of ghost in the machine, which I have always found kind of fascinating. In a way my work has always been informed by this relationship between technology and spirituality, only I feel my work doesn’t fit into the established aesthetics of a technology artist. But in a sense, the parties and the way that we worked…. in 2004/5 I was primarily concerned with how to present a network of people as an artwork.

diga.rt: Well it’s funny because I thought of your work so easily fitting into this publication, but I guess it might not be as obvious as I think it is.

MS: We seem to be marching ever further towards a materialist worldview, but are somehow using materialism to literalize these previously spiritual ideas. I mean with the internet there’re these massive parallels with the mystic ideas of a vast, interconnected consciousness. I’m interested in the metaphysical, but I always want to bounce it back into materiality.

diga.rt: Well the reality is that it plays out in haptic space anyways. We may have different understandings of community that are based around things like aesthetics or whatever that exist through these immaterial spaces, but they ultimately play out as we walk around on the street.

MS: Exactly.

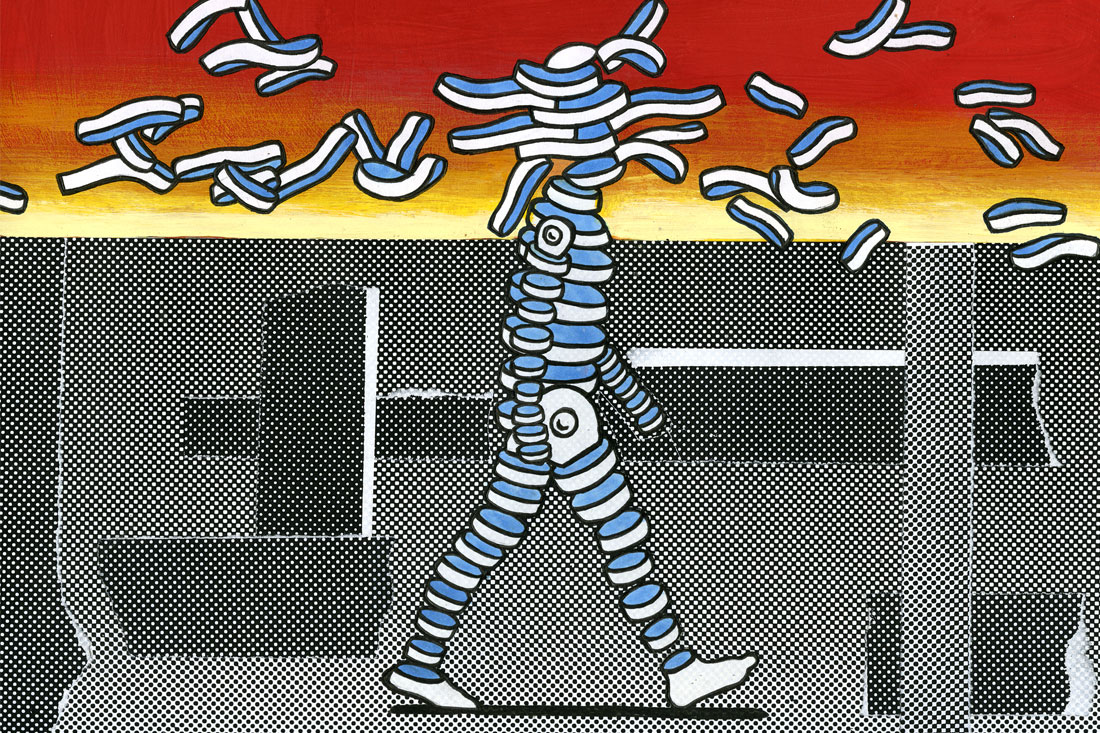

diga.rt: I’m curious to hear you talk about your more recently-exhibited body of paintings.

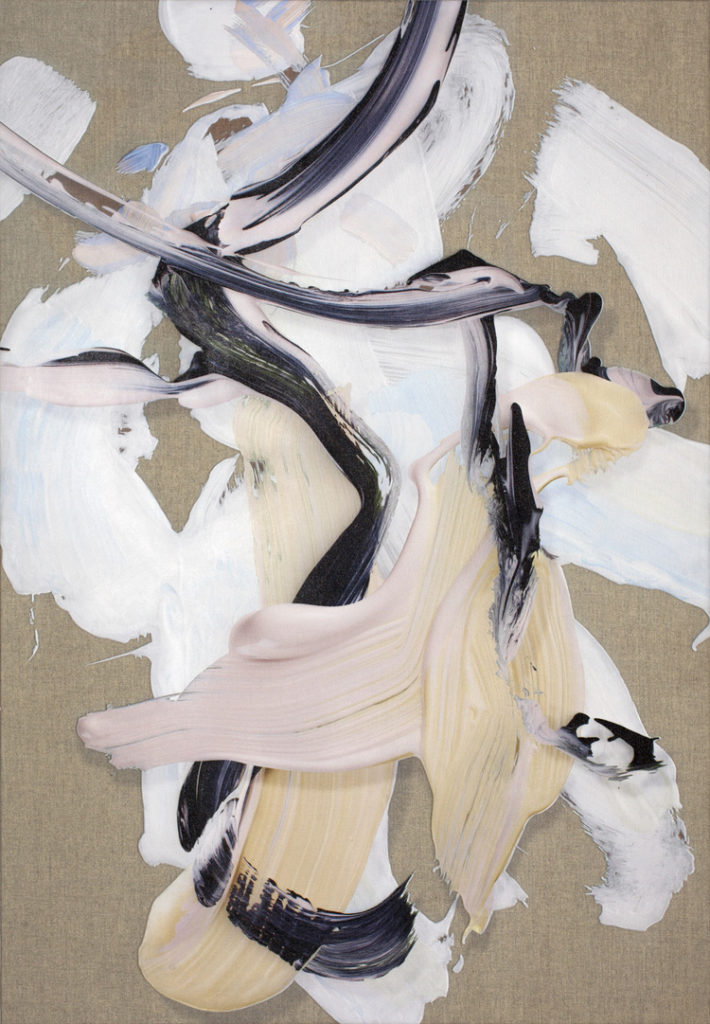

I saw them when they were exhibited at The Hole [Editor’s note: Link no longer available], and because they’re digitally printed they superficially have a Lichtenstein sort of vibe to them; yet, again, they don’t seem to be mocking the Romanticism of Abstract Expressionism for example….

In contrast to expressionism however, the presence of the artist’s hand is pretty different. I guess what I mean is they seem to have a romantic quality to them, but one that is less invested in expression or authorship and more about the beauty of paint itself.

MS: They start as an offline process where I’m physically painting on glass, and then they’re digitized and processed in Photoshop. In a sense I’m trying to find what I can do in Photoshop that extends the language of painting, so that when you look at it, it feels like it could be paint, but actually there’s a whole series of impossibilities embedded in the work.

They process a lot of redundancy. They take on the redundancy of heroic Abstract painting, the redundancy of a printed version of a painting – and they use those to unlock a space to almost get that sense of the inert out of the way. In a similar way to the performance we discussed earlier it creates a space where people can see painting in a different light.

I feel like artists are constantly trying to find a way to make paintings that aren’t cheesy. I’m not trying to manufacture a lifestyle around the work that justifies me being allowed to pretend I’m making paintings in the 50s, and they recognize that this isn’t possible. But the work sort of suggests that there are spaces in our times where these things might still live or feel relevant.

I think I’ve also realized that with these works I’m sort of on hiatus from the human form. I mean I knew that by working with paint rather than bodies it freed me to work in the studio every day, and to make work every day. It wasn’t based around other people’s schedules…. And it allowed me to highlight the difference between using materials and working with people, because there’s no real room for abuse with paint.

But then a friend of mine, the artist Phoebe Collings-James, said, “Do you think you just needed a break from the politicized nature of bodies?”

And the thing is that every body has signifiers that suggest established ideas of gender or ethnicity, and while what is suggested might not always correlate with that individual’s identity, I think I needed time to think about the ways in which I process that, and how I handle the implied hierarchies that emerge.

You know, if a woman puts her hands over the eyes of a man, what does it mean?

diga.rt: Yeah, there’s suddenly iconography there…

MS: Right. And so much of it is bound up in bodies. And I think I was always (perhaps naively) projecting to a space beyond that. I think that in one sense there’s a need for imagery that tries to go to that place, but in another sense I have an increased sense of the responsibility that comes with doing so. I started to think whether or not it was responsible to be implying a post-racial, post-gender space in my imagery.

I wasn’t conscious that my awareness of this was instrumental in my decision to make abstract imagery over the figurative. So I feel like it was a particularly lucid question or statement that she made.

diga.rt: It’s interesting how similarly both bodies of work function. I brought up Abstract Expressionism because although the paintings have brushstrokes, there doesn’t seem to really be the presence of the artist’s hand in a sense. The brushstrokes appear more like independent figures….

MS: There is this sense of movement with both the bodies and the paint. With the photographs I was taking – when I looked through the camera I would blur my eyes, because I didn’t want to read the image as literally figurative – It wasn’t about traditional portraiture. I was trying to project towards an abstract space. I wanted to use the body to go beyond a materialist way of thinking. I used the body to go beyond the body, and to try to track the networks of subtle energies and interactions, communications…

diga.rt: That can be seen.

MS: Yeah. And the challenge is to take the things that we think we know the most. I mean it’s pretty obvious that if you look at the history of art, and if you expand the definition of art to include all images, the body is omnipresent. I wanted to abstract the body. So in one sense I understand everything I’m doing with the paintings. But in another sense, in a personal and romantic sense, I feel like I’m still painting the energy within bodies, and the energy that moves between bodies.

I’ve always felt like there are two people inside of me and the other person is coming out now. One of those people is rational to a certain extent, and kind of able to rationalize what I’m doing and what it means and how it might affect people. But there’s another side of me that’s purely mystic, and that’s existed as a part of me since I was a child. That part of me is interested in healing and energetic interconnection.

I feel like I’ve always had this intellectual understanding of emotional intelligence. But recently I feel like that intelligence has sunken into my own body.

diga.rt: That’s exciting.

MS: Yeah. It’s been really humbling in a sense. But I feel like I’ve spent my life talking about a lot of things – making a lot of grand statements about a lot of things… But I feel like I am at the very beginning of understanding a lot of the things I’ve talked about in the past.

So that idea of the artist as shaman… I feel like a lot of good ideas start out as jokes, ‘cause then you have to step up and fully become them. I feel like I’m still very much stepping up.