In the written piece, Can Radio Help Us Become Forest? (2021), Sarah Schmitt examines ways to create support systems for all communities, specifically non-digital communities, in a digital world. With accompanying illustrations, Schmitt seeks collectivism after a “pandemic of individualism” and remote social culture. In this piece, readers can ponder how digital technology can be used to unify isolated communities.

:::

Can Radio Help Us Become Forest? Imagining Cybertariat Psychosocial Solidarity in Low Fidelity

The Forest As Mesh Network and In Defense of the Lo-Fi

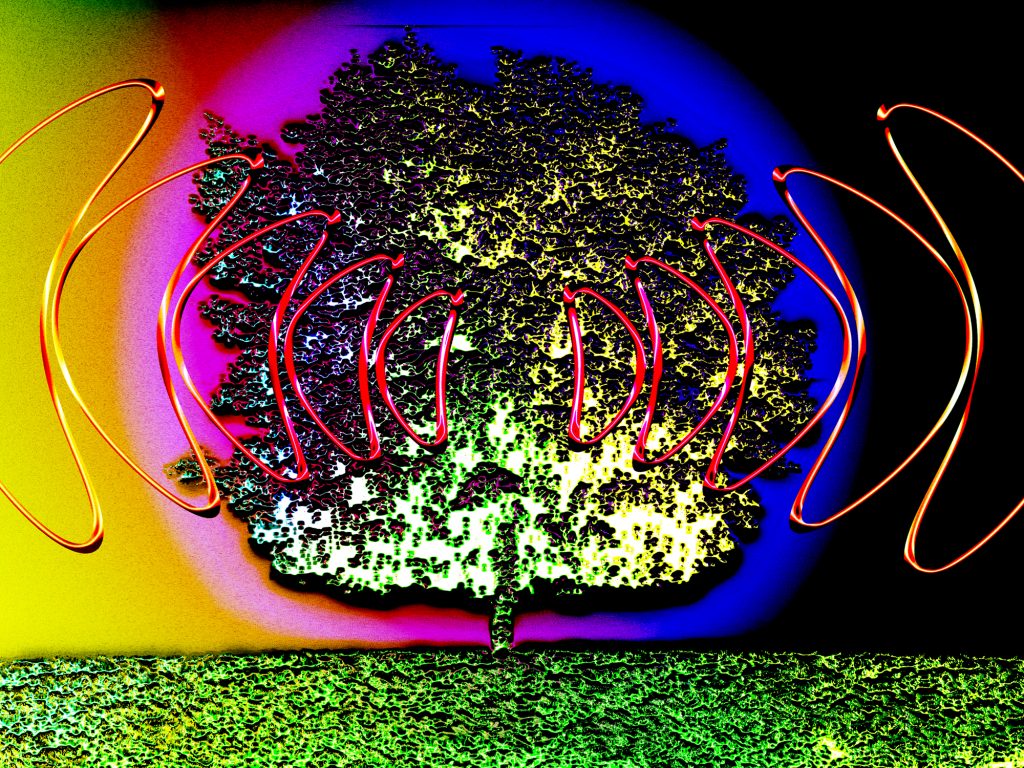

Ecologist Suzanne Simard discovered that trees communicate and redistribute resources through a “network of latticed fungi buried in the soil.” Through this naturally occurring mesh network, trees send warning signs to each other, transfer their nutrients to neighbors as they die, sabotage unwanted plants by strategically distributing toxic chemicals, and send carbon towards shaded seedlings—a support that without which, the baby trees would be unable to survive. Trees in forests “are not individuals.”1 They connect with each other, communicate their needs, redistribute resources, and help rear their young—all for the good of the forest as a whole.

Can radio help us become forest?

This is a proposal for something part real, part science-fiction-daydream. We let the radio be our latticed fungi. I am imagining a new model for remote psychosocial support, a mutual-emotional-aid ham radio network. A contributive, electromagnetic space for sharing—without the information dodgeball of contemporary social media platforms—that connects us to other digital persons as well as non-digital persons. This arboreal-radio-daydream is decentralized, it is against growth-fetishism, it is counterindustrial, and it is outside of the economy of surveillance capitalism and this economy’s affair with the panoptic, confessional, parasocial world of Instagram and its cousins. A world that is interconnected, empowered by its tools, that shares, that creates—not for the sake of infinite progress, but for the enrichment of the community-forest.

Preceding the Doom Times, technology was already accused of creating an increasingly socially isolated and disconnected world. Now, there is no debate about isolation. We have all felt it. An aching fit of dread, sometimes sharp, sometimes dull, embedding itself into our new normal. Perhaps in this moment, social-computational globalization plays in our favor. We can’t see anyone, but we can go on Instagram. We can simulate social interaction in between barrages of advertisements by engaging with posts of people we know, admire, or hate follow. We forget, though, that even some of us with technological access lack the technological literacy required to enjoy (or despise) this digital psuedo-commons.

How do we build a remote psychosocial support system accessible to non-digital persons? Can we make this remote psychosocial support system exist outside of the “cloud feudalism”2 of technocratic centralization? Can we innovate with the analog? Can radio help us escape the pandemic of individualism? Can we de-grow remote social culture during a pandemic? Can we (de-)grow into a forest?

The Radio I: Cult Radio

In March I was redesigning Cult Radio. It’s an online radio with a playlist curated by our Creative Director, Julian Casablancas. The concept behind the radio is to have a place for people to enjoy music without ads and without algorithms. The music varies. “Smalltown Boy” by Bronski Beat plays after indie bops by Metronomy, followed by Os Mutantes, a politically dissident band from 1960’s Brazil.

It was peak Badness in New York City. My birthday was coming up, I was angry all the time, and I didn’t know how to process everything—especially without knowing the next time I would see my family. My folks are in Georgia, where the Governor’s Trumpian rhetoric has a bodycount. My formerly alcoholic 73 year old Godmother who never answers her phone locked herself in her house. It is what she had to do—and given the infection rates in Atlanta right now, it is what she still must do—but thinking of her aloneness created a vacuum in my gut, sucking me into myself. My stomach and my soul ached, and I would get my design work done in between mood swings and bouts of ravenous hunger.

I started looking at old radios: their knobs and switches, at 80’s ghetto blasters and their volume visualizers. I started thinking about radios: people sharing musical and emotional experiences from different, though proximate, locations. Cult Radio is a radio that is nominally liberating in the context of a supercapitalized music industry. I started imagining radio’s other potentials: radio delivering us from our physical isolation, from the closeness-but-distantness that we must maintain for all of our sakes. What if we could transmit our sorrows? Our Joys? Can lo-fi emotional proximity reconnect us? Could radio waves be our mycorrhizal network—sending word of love, laugh, affection, distress while we grow roots in our homes? Could Radio help us create a post-Pandemic, “subtractive[ly] [modern]”2 electromagnetic commons?

The Mental and Physical Toll of Loneliness

“Meals continue to motivate me. I am also drinking heavily. For right now, it can’t be helped.”3

It is no secret that loneliness is bad for us. The irony of human contact being good for our health while we must reduce human contact for the sake of our health is not lost on anyone. Isolation has an even higher toll on the most vulnerable members of our communities. According to the U.N. Policy Brief on Covid-19 and the Need for Action on Mental Health, “Loneliness is a major risk factor for mortality in older adults.” Additionally, social isolation, having less active lives, and fewer intellectual stimuli increases “the risk of cognitive decline and dementia in older adults.”4 It is unfair that we must encourage our elderly loved ones to stay home and socially distance in the non-safety of their loneliness. Unwittingly, and for lack of an alternative, we usher our parents and grandparents into the throes of a different risk, one that is still deadly, just slower.

In New York, it has been a summer of loneliness and togetherness. We were locked inside until political circumstances demanded something else. The streets had been deserted, and suddenly they were full. It was like whiplash. There was something vigorous, though, in the necessary collective expression of anger for Black Lives. I will not compare the pandemic of police brutality to the pandemic of loneliness; they are distinct—though not discrete—systemic problems both deserving of close, compassionate, and critical examination. What interests me is the feeling of being home, rotting with anger, and then walking outside to share that anger with the world, with the sometimes fifty, sometimes thousands of other people that are walking with you. Those moments, though they do not assuage systemic issues overnight, do assuage the spirit. They are a redistribution of psychic burdens. Expressing solidarity, sharing your anger, and taking on someone else’s is a vigorous feeling.

Maddy Loat proposes in her book “Mutual Support and Mental Health: a route to recovery” that mutual support groups offer a meaningful contribution to mental health therapy, on its own or in conjunction with other treatments.5 These social support groups, where participants are encouraged to share their experiences with others, help create a sense of belongingness in a non-hierarchal settings. They strengthen bonds, build interdependent and empowering relationships and foster “collective responsibility for each other.”5

Walkie-talkies, with all of their chaotic potentials, are inherently non-hierarchal. They are a system for transmission and receiving, and then a reciprocal transmission, if the participant desires. No one’s transmission is prioritized over another’s, and the devices can be turned off or on at one’s leisure. How do we social distance without losing emotional closeness? How do we safely redistribute the psychic burdens of our elder loved ones right now? Can we use the non-hierarchal nature of the two-way radio to create community driven, democratic psychosocial support systems? Can we use low fidelity communication to build solidarity in our communities? Can we assuage loneliness electromagnetically?

The Radio II: Joyous Potentials, or Walkie Talkies as Convivial Technology

“Progress should mean growing competence in self-care rather than growing dependence.”6

The philosopher, social critic, and Roman Catholic Priest Ivan Illich writes in his book “Tools for Conviviality” about a concept called “radical monopoly.”6 “Radical monopoly imposes compulsory consumption and thereby restricts personal autonomy. It constitutes a special kind of social control because it is enforced by means of the imposed consumption of a standard product that only large institutions can provide.”6 Smart phones and social media have overtaken the world in a way that satisfies this definition “compulsory consumption.” With the loss of net neutrality (in the US), the growing internet gig-economy, and our economic and social dependence on the internet, we are seeing power structures replicate themselves in and around cyberspace. Simultaneously, in a tornado of social media advertisements and allegations of internet psy-ops, the dream of an emancipatory world wide web fades from our imaginations .

llich writes about another concept, “conviviality.” He writes that convivial is a “technical term to designate a modern society of responsibly limited tools.” “Tools foster conviviality to the extent to which they can be easily used, by anybody, as often or as seldom as desired, for the accomplishment of a purpose chosen by the user. The use of such tools by one person does not restrain another from using them equally. They do not require previous certification of the user. Their existence does not impose any obligation to use them. They allow the user to express his meaning in action.”6 In the use of convivial tools, one can find joy.

I postulate that the two way radio, the walkie talkie, is the convivial tool to the radical monopoly of the smart phone. Walkie talkies are easy to use. They are robust technologies that rely on electromagnetic waves to transmit a sound to a receiver, and, if the receiver is inclined, they can reciprocate this action. The physics of electromagnetic waves is unchanging. Walkie talkies suggest no obligatory consumption; they are playful, simple, and relatively accessible devices. They are even easy enough to repair, if you are so inclined! And there is a lively ham radio community that would be glad to help with such a project.

In a world of too-much, of infinite progress, of technological solutionism, where “innovation” is defined as getting us closer to the hyper-technological-Elon Muskian-fantasy-future of flying cars, perhaps we can find something liberating in slowing our technology down. A slower, if still technological solution, better suited to “creative intercourse among persons, and the intercourse of persons with their environment.”6 This project proposal is one for an intergenerational experiment in the re-tooling of society.

Conclusion

I am imagining what it would look like if this really caught on. Alongside intentional conversations and tender exchanges there would also be moments of chaos, interruption, as well as unexpected connections. Walkie-Talkie radiowaves are shared by everyone who is inclined to participate. The possibilities of these accidental interruptions are endless; someone else on your frequency is just as likely to annoy you as they are to make you laugh.

One month into quarantine I walked an hour through Brooklyn to my best friend’s apartment to hang out on her roof. I had not seen anyone I knew other than my roommates for weeks. My friend lived alone at the time and had seen even fewer familiar faces. We were on her roof, enjoying the stolen luxury of each other’s company—something that would have been a regular afternoon a couple months prior.

On the other side of the roof was a couple. We were out of each other’s eyesight, but we could hear them. They heard our meandering, increasingly drunk conversation, and we heard them. They were rapping, singing, screaming, flirting. They talked about the Sun. Our adjacency resulted in a sort of cross-pollination, even though we did not speak. We got to safely enjoy the contingencies inherent to existing in public space for the first time after a month of strict isolation.

I like to think that a blip on a walkie talkie from another person, a child screaming over the radio waves, or accidentally over hearing another’s conversation, is an electromagnetic translation of these contingencies. Walkie talkies allow space for pleasurable invasions of the expected. They recreate those moments when you encounter strangers—the benevolent connections formed with people you’ll never see again, the anticipation of a maybe-hello, the breath when you meet someone new who you know nothing about and the possibilities are banal, chaotic, endless.

Radio has the potential to become a dense, oxygenated space that can connect us with our elders and our seedlings. Looking into our precarious futures, I hope we can begin to innovate responsibly and sustainably. I hope we begin to take advantage of the robust technologies we already have, rather than chasing the cancer of infinite progress. I hope we look to the forest as a model for our networks of the future: an interdependent, dense, compassionate mycorrhizal lattice that can help us offload our psychic burdens. I hope we can find social proximity in our social isolation, that we can de-grow into something greater, more self-sufficient, and harmonious. This project is a facilitation of the metamorphosis from radio to fungus—to help us find psychic peace while we root.

Works Cited

1 Menezes, Fino. “Discover How Trees Secretly Talk to Each Other Using the ‘Wood Wide Web.’” EcoWatch, EcoWatch, 19 June 2020, www.ecowatch.com/trees-communicate-2646209343.html?rebelltitem=3.

2 Bratton, Benjamin H. The Stack – On Software and Sovereignty. MIT Press, 2016.

3 Schmitt, Sarah. “Quarantine Journal.” New York, New York, 16 Mar. 2020.

4 “Policy Brief: COVID-19 and the Need for Action on Mental Health.” The United Nations, 13 May 2020.

5 Stephens, Paul. “Mutual Support and Mental Health: a Route to Recovery.” European Journal of Social Work, vol. 16, no. 2, 10 Apr. 2013, pp. 306–308., doi:10.1080/13691457. 2013.785700.

6 Illich, Ivan. Tools for Conviviality. Marion Boyars, 2011.

:::

Sarah Schmitt is an artist and designer from Atlanta, GA, based in Brooklyn, NY. Her research-based, multimedia practice examines cultural & technological de-growth and alienation from the natural world. Her works—spanning writing, performance, video and textile—are an eco-gothic remark on extractive economies and the rift between the (Western) human world and the non-human world.