Digital America is excited to publish Norberto Gomez, Jr.’s exploratory manifesto on the 21st century art machine. We have done our best to bring life to the materiality of the original, hand printed book, and we look forward to publishing the subsequent chapters over the next few months (see the end of the piece for a preview). Here, Norberto plugs us in to the recent history of artist/pop culture feedback and personal branding since Dylan went electric. Today, he explains, “social media and the self-commoditization of our own identities” compels artists to adopt PR lingo describing “our network” and personal “brand.” This feedback grows tighter with the ubiquity of computing and promotes a “new international style brought on by glocalism, city worship, boundaries, the nomad versus the scenesters.”

Enjoy.

***

I got my dark sunglasses

I got for good luck my black tooth

I got my dark sunglasses

I’m carryin’ for good luck my black tooth

Don’t ask me nothin’ about nothin’

I just might tell you the truth

~Dylan

When Dylan went electric, Dylan went black.

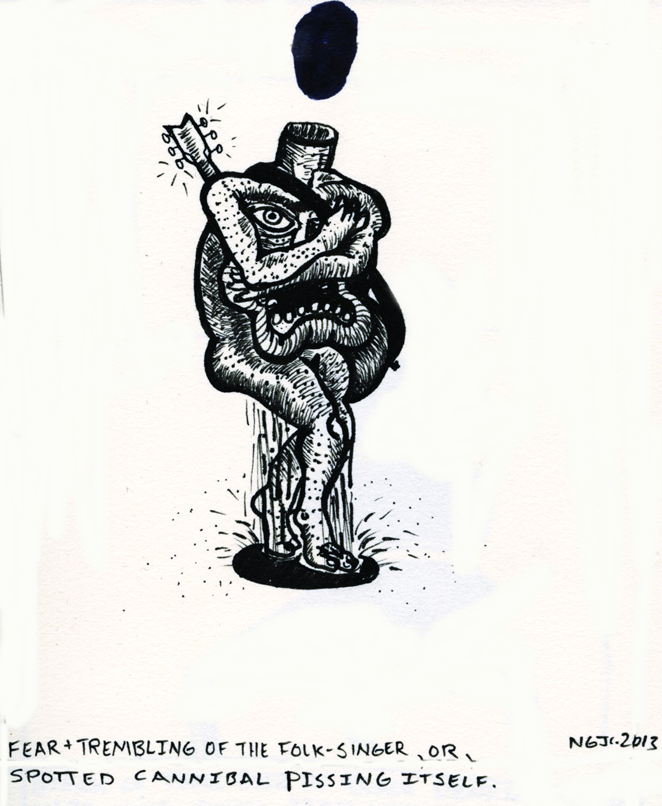

This moment was not simply about “going electric,” rather, Dylan can be said to have gone rogue, gone cannibal, gone underground, interstitial, and nomadic.

Clearly, the media references this single moment as pivotal (theatrical), when in fact, it was and continues to be a process. The popular biography of Dylan describes his hunger for certain ways of life, of being, of identity shaped out of various sources: parts of Guthrie, Elvis, Johnson, Rimbaud, Odetta, and other facts and fictions spun by the artist and others. Is this not every one of us? Should this not be all of us?

We lose friends in the process.

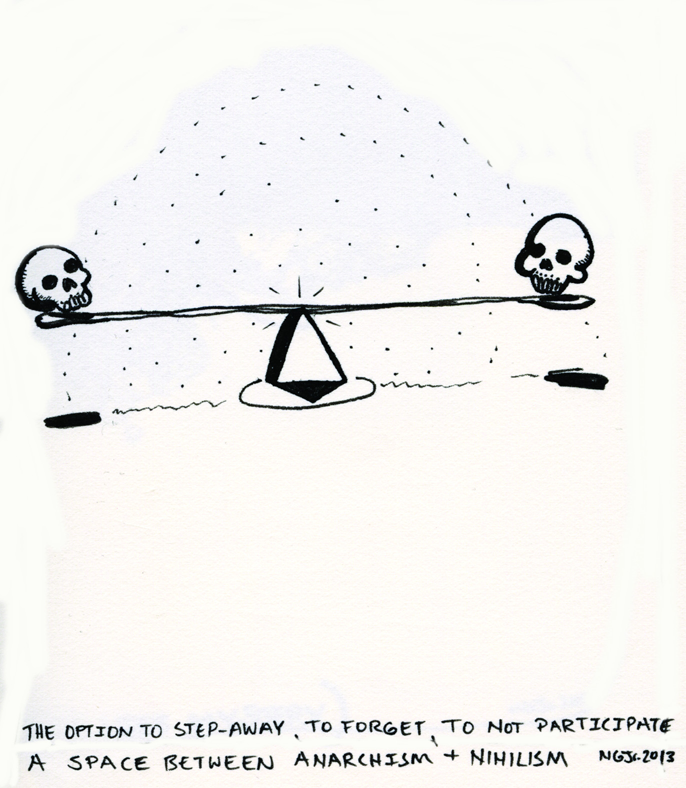

The artist became bigger than ever by paradoxically stepping away. On the other hand, the Beatles became more socially engaged, with their stepping away expressed instead in their musical experimentations. The music was out-there, but they struggled with their identity and political-reality in the process. This is especially true for Lennon, who for many years fought for American citizenship. It remains a miracle that the weirder The Beatles became, the more popularity they achieved. The same could be said of Radiohead since Kid A (2000). Perhaps, it is all timing. Dylan’s act, however, should not be confused with his actual period(s) of hermitage. Rather, the artist chose when and how to play to various realities, when and how to dip into certain scenes, styles, consciousness, and media. The cannibal asks for the same from you. Where and what are the spaces between anarchy and nihilism? Do we fight within a programmatic reality or do we disappear, immersing ourselves in nothingness? And, oh, how voluptuous and sumptuous is the call of nothingness –we should all visit from time to time.

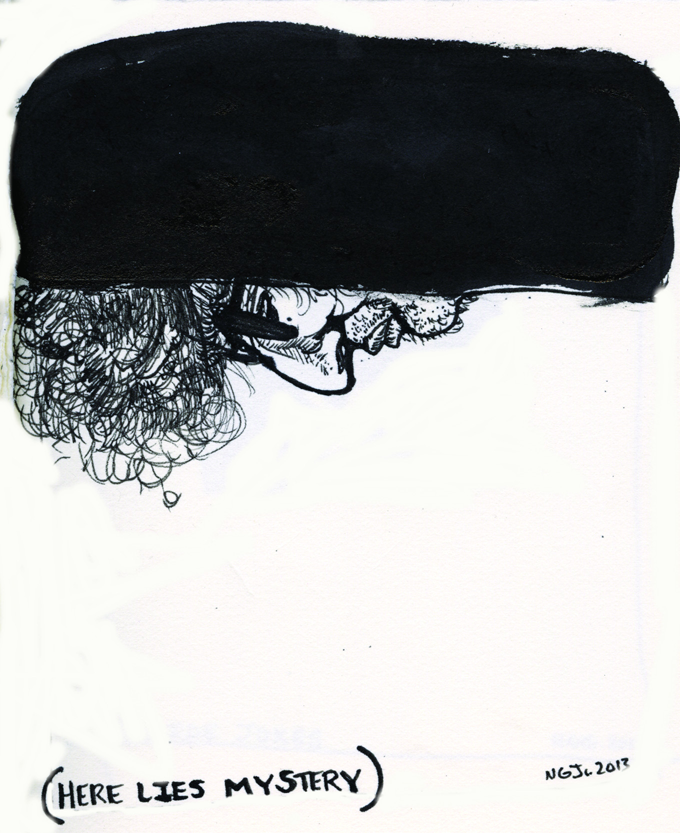

Dylan wore black, with black Ray-Bans, and levitating hair he bathed himself in the honesty of mystery. Thus, truly he composed his greatest works while being there and not there, simultaneously. Today, when all media is considered social and everyone is their own public relations agent, how is the artist to proceed? The social-artists cannot allow for another Dylan, and this must be their call (in 140 characters or less):

DEATH TO BOB DYLAN; LONG LIVE ROBERT ZIMMERMAN

Mystery is dead. Mystery must be reanimated.

The image of Dylan which persists is that of the folk artist and/or protest singer. It is the image of a (typically) young musician (almost always male) behind acoustic guitar singing for looped social content and justice. Whose justice? And, over and over and over again, so goes the story. The state of the political-artist is one of archetypes, structures, systems, and formulas required of the political-reality. One may call it recycling, but perhaps that is closer to what Dylan did/does with early Americana, African American blues, and Romantic poetry, because with recycling we have a different end-product. Political-reality, on the other hand, features the political-artist, who is a different myth, or character, both formulaic and typically trite –the sound bite. It is performative in a way only useful for “getting along” in an awful political-reality. Its production is mass duplication and sloganeering.

The results are embarrassing, as with Conor Oberst’s (Bright Eyes) “When the President Talks to God,” (2005) featuring these lyrics:

When the president talks to God

Are the conversations brief or long?

Does he ask to rape our women’s rights

And send poor farm kids off to die?

Does God suggest an oil hike

When the president talks to God?

Here we have the narrative of the “poor farm kids” in lyrics which seem to refer to a compressed, collaged history of all wars, all presidents, all Gods, but not as a comment on the human condition, but, instead, it is more of a confused history or lack of difference in which the singer believes the current situation to be unique and yet Vietnam all over again. Oberst goes on to criticize the theatrics of political-reality, asking, “When the president talks to God / Does he fake that drawl or merely nod?” All the while, a late night host introduces Oberst with, “Tonight he is singing his critically acclaimed protest-song,” and the singer stands alone with cowboy hat, western style shirt, and acoustic guitar, costumed for the ritual of this protest-process, he sings in his exaggerated, stylized way, as is his role.

This complicated expression of this nostalgic history, as described by Jameson, results from a culture of the simulacrum, which has an “appetite for a world transformed into sheer images of itself and for pseudo-events and ‘spectacles’…” He continues, “The past is thereby itself modified: what once was… has meanwhile itself become a vast collection of images, a multitudinous photographic simulacrum.” In this case then, our folk-singer is “condemned to seek History by way of our own pop images and simulacra of that history, which itself remains forever out of reach.”

This is the despotic political-reality Dylan massacred with his axe. He saved himself in the process, only to be reborn each day ever since, sometimes cataclysmically so, as with his transfiguring motorcycle incident. Rock-n-roll was, yet again, rejuvenated. Why would this turn cause such a disruption amongst his contemporaries and friends, like Pete Seeger, who continues the same old tired system and criticisms of Dylan’s post-protest material? Besides envy, the answer is the fear of the other, the fear of the cannibal, of what one does not have or can never have. Why is that bad art, while this is good art? Je ne sais quoi; it is unnamable, but we all recognize it. Dylan was never Christ, but perhaps he is the anti-Christ. The jealousy and envy caused by this cannibal who rebelled against the rules of the political-reality after having it all terrified others. He could have had acolytes; he could have ended all wars. All he needed to do was not be himself –speak for everyone else!

In a letter to Dylan, Irwin Silber wrote:

…any songwriter who tries to deal honestly with reality in this world is bound to write “protest” songs. How can he help himself?

Your new songs seem to be all inner-directed now, inner probing, self- conscious — maybe even a little maudlin or a little cruel on occasion. And it’s happening on stage, too. You seem to be relating to a handful of cronies behind the scenes now — rather than to the rest of us out front.

Now, that’s all okay — if that’s the way you want it, Bob. But then you’re a different Bob Dylan from the one we knew.

In 1965, Silber inadvertently answers his own charge, for profoundly Dylan doth protest. Unfortunately, Silber’s folk-singer lives on as a standard mode of production for those who have not recognized the looped nature of political-reality. The media has chosen to dispense of the competing image of a cannibal-Dylan, who lives and continues to compose and tour. Thus, during each period of war or unrest the headlines read, “Where is Our Dylan?” or they declare, “This Generation’s Dylan,” as if he died July 20th, 1965, Newport, RI.

Requiescat in pace. We never truly knew thee.

Therefore, today, it is the Ghost of Dylan who haunts singers and songwriters. This older, poltergeist fellow dipping in and out of categorical lines is something of a nuisance, but no one can look away, no one can stop listening. Even the singer’s voice is ragged and worn with age. Many will say his voice was never his strong suit, thus, it has always been one of his strongest suits. Today he continues to deny us our expectations by radically reconstructing his “greatest hits” live in such a way so as to be unrecognizable by those who expect absolute repetition. The audience is stunned and made uncomfortable by “Tangled Up in Blue’s” disappearing melody, and its more meandering and complicated structure. They lean in trying hard to listen for something, anything familiar as he releases guttural staccato verses. When the chorus is given there is a mass sigh of relief, but they are left with existential angst. How dare he? (In fact, how dare he die, i.e. age, before us? There is more comfort in his immortal folk-singer image.)

Sadly, but expectedly, musicians of the 1960s, like Seeger, often return feeling a duty and responsibility to remind everyone of dead wars (and, in the process, they remind us of themselves –one wonders if they actually hope for unrest, as chaos and strife have become nostalgic, a reminder of their former relevance). They act dumbfounded when older systems appear unworkable within the current –kids these days. The protest-singer simply legitimizes the system, as does reforming the State’s institution of marriage, or choosing anarchy, but, “the whole key to liberation is magic,” writes Robert Shea and Robert Anton Wilson. “Anarchism remains tied to politics, and remains a form of death like all other politics, until it breaks free from the defined ‘reality’ of capitalist society and creates its own reality.” In this case one might consider nihilism to be the necessary extreme, but not the nihilism of a previous century, but something closer to the recent nihilism described by Jean Baudrillard as a form of transparency:

and it is in some sense more radical, more crucial than in its prior and historical forms, because this transparency, this irresolution is indissolubly that of the system, and that of all the theory that still pretends to analyze it. When God died, there was still Nietzsche to say so – the great nihilist before the Eternal and the cadaver of the Eternal. But before the simulated transparency of all things, before the simulacrum of the materialist or idealist realization of the world in hyperreality (God is not dead, he has become hyper-real), there is no longer a theoretical or critical God to recognize his own.

Today, Dylan is charged as plagiarist in both text and image. As if the lessons of folk borrowings never mattered, as if the artist never admitted to inspiration. As if appropriation in art were never a strategy. As if bricolage is a new sin. As if the protest-singers of political-reality were not merely the copies of a copy. Dylan, on the other hand, is the epitome of cannibal –acknowledging those he has consumed –this is nothing new. Instead, Dylan makes active his relationship with “influence,” a term art historian Michael Baxandall[i] critiques as passive, and in response gives us a list of other more suitable words and phrases.

Dylan will:

1) DRAW ON

2) RESORT TO

3) AVAIL ONESELF OF

4) APPROPRIATE FROM

5) HAVE RECOURSE TO

6) ADAPT

7) MISUNDERSTAND

8) REFER TO

9) PICK UP

10) TAKE ON

11) ENGAGE WITH

12) REACT TO

13) QUOTE

14) DIFFERENTIATE ONESELF FROM

15) ASSIMILATE ONESELF TO

16) ASSIMILATE

17) ALIGN ONESELF WITH

18) COPY

19) ADDRESS

20) PARAPHRASE

21) ABSORB

22) MAKE A VARIATION ON

23) REVIVE

24) CONTINUE

25) REMODEL

26) APE

27) EMULATE

28) TRAVESTY

29) PARODY

30) EXTRACT FROM

31) DISTORT

32) ATTEND TO

33) RESIST

34) SIMPLIFY

35) RECONSTITUTE

36) ELABORATE ON

37) DEVELOP

38) FACE UP TO

39) MASTER

40) SUBVERT

41) PERPETUATE

42) REDUCE

43) PROMOTE

44) RESPOND TO

45) TRANSFORM

46) TACKLE

In a recorded interview found on the bootleg Great White Wonder (1969, King Kong Records), Dylan explains his writing process:

…I don’t even consider even writing songs…I don’t even consider that I wrote it when I got done … I just figure that I made it up or I got it some place…The song was out before me, before I came along. I just sort of came down and just sorta took it down with a pencil, but it was all there before I came around. That’s the way I feel about it.

Ever since the death of protest-Dylan the acoustic guitar has taken on the mythos of the organic, the natural as symbol for the working class, for the one who tills thy land (who even knows what that really is anymore; isn’t farming dead in the New World?): the naturalist, the lonely traveler, story teller, Heraclitus, or Socrates, and Christ. When our new folk singer arrives, as is inevitable, it is with acoustic guitar strapped to their back, as with Guthrie before. The wood represents its former life as rooted in the ground of mother Earth from whence we all came. Nothing else can be as honest as the words and music naturally amplified from the body of a tree. They insist you listen in, step up close, and pay attention, because the words ring true, and this is their song:

THIS MACHINE KILLS FASCISTS!

But what more does it do now than to impose the protest-singer and the political-reality upon one’s shoulders -violently, impossibly, and uninvited? We respond:

THIS MACHINE IS FASCIST.

[i] “Excursus against influence,” Patterns of Intention: On the Historical Explanation of Pictures, (1985).

***

Up Next:

Norberto describes the next chapter of the book as a critique of social listening spaces and standards of digital listening experiences. Exploring the phenomenon of temporal compression, he introduces us to the SUNN O))) concert experience, which serves as a counterpoint to “our saturated psycho-geographical social relations.” The band SUNN O))), playing incredibly slow and incredibly loud,

act as facilitators of the rebirth of time and space, for not only is the sensation of listening emphasized, but it is coupled with the physicality of music whereby the experience of hearing coincides with vibrations of one’s body hairs, and tickling ear drums. It can be tiring and complicated as with any important and invigorating experience –like near-death experiences, or especially in this case, rebirth –a total destruction of virtualization.

Stay tuned…