“…I am always reminded of how small changes in the details of a digital design have profound unforeseen effects on the experiences of humans who are playing with it…It is impossible to work with information technology without also engaging in social engineering.”

-Jaron Lanier [1]

After a relatively quiet and unmourned death, the chatroom as a social space recently returned in the form of Omegle and Chatroulette. The classic chatroom of the 1990s was overtaken by other platforms as the WWW moved to newer forms of sociality; namely, the social network. These later social web platforms have taken the place of self-made homepages devoted to the individual. No longer content to be members of specialized forums and bulletin boards, users opted instead for global citizenship featuring profile environments –the WWW’s version of a passport, or ID.

I remember a time when the Internet of the ‘90s was filled with various spaces of sociality, catering to specialized categories and celebrities, likes and dislikes, somewhat chaotic and inundated with an overuse of graphics and early animation –it was a space to get lost in. Users created and maintained identities with meaningful usernames and chat handles, or pseudonyms. We may argue that this is the same today, and in some respects it is, but with the rapid standardization of browsers, the decline of homepages, the progress of mobile networking, and success of a few number of social networking platforms there can be no doubt that over the last decade our network has significantly changed our interactions and therefore personal identities.

Instead, today in the electric age as foretold by Marshall McLuhan, we mostly get lost in one another’s information because “electrically contracted, the globe is no more than a village” in which we are “eager to have things and people declare their beings totally.”[2] But it is clear that this “declaration of being” may be less about a deep faith in the “ultimate harmony of all being,”[3] and something closer to narcissism, voyeurism, and/or the most blatant example of the commoditization of one’s own identity. It is accepted practice that we are to monitor our daily digital interactions as if our life depended on it, and indeed, often it does. We are full-time public relations agents representing ourselves.

Stepping outside the walls of this global village, in search of a return to the individual, nomadic cyber surfers of an earlier networked era seems counter intuitive to the branding and marketing of our digital democracy, but with the eruption of online spaces which facilitate anonymity, or the stranger, and an increase in privacy concerns, it appears that more and more users are experiencing an identity crisis –but which one?

The Dead Zone: The Death of Yahoo! Chat

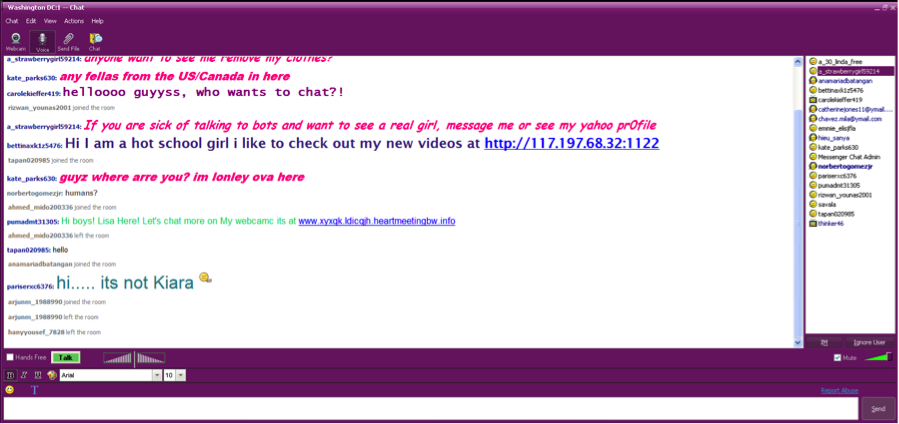

Yahoo! Chat, once a thriving enclave, is like a living monument to another era, a ghost town overrun not by chatters per se, but by chatbots. Whole rooms exist with various themes, topics, sub-topics, and subject matter with rarely a living human in sight. One can’t help but imagine bot-2-bot conversation, an endless loop of automated responses, ad infinitum. It becomes blindingly clear who is real and who is not based on various elements of the both the user’s chat handle as well as their vernacular. Somewhat romantically, these purveyors of, almost always, pornography are stuck in the language of a pre-social web, using presently dead styles, like “kewl.” Ironically, their language is either a caricature of netspeak, or their grammar is too proper, too proper to be human.

The goal of bots is to promote and link users to certain content. In Yahoo! Chat this means, primarily, adult websites, i.e. pornography: videos, camgirls, with all requiring “free” credit-card registration (just to verify age, of course). With the number of bots proliferating in the rooms, there can be no doubt that at some point we failed the Turing Test. In fact, we failed it long ago:

norbertogomezjr (4/4/2012 8:57:16 PM): are you a bot?

[A transcription of a Yahoo! Chat between the author and chat-bot, April 4, 2012.]

a_strawberrygirl59214 (4/4/2012 8:57:20 PM): wtf, im not a bot

norbertogomezjr (4/4/2012 8:57:46 PM): i’m sorry. what are you?

norbertogomezjr (4/4/2012 8:59:09 PM): are you there?

a_strawberrygirl59214 (4/4/2012 8:59:11 PM): i cant open my cam here yahoo wont allow it cause its adult – but you can access it on my profile

norbertogomezjr (4/4/2012 8:59:35 PM): I thought you weren’t a bot?

norbertogomezjr (4/4/2012 9:00:59 PM): Are you there?

a_strawberrygirl59214 (4/4/2012 9:01:09 PM): i cant open my cam here yahoo wont allow it cause its adult – but you can access it on my profile

Last message received on 4/4/2012 at 9:01 PM

Sometimes the bots surprise me, as their responses and use of language is slowly updated by a mysterious figure: for example, I was once asked, “Who you callin’ a bot?” Yet their creators remain wholly unknown and unquestioned by users. If their dialog, among other features, is so easy to single out, why bother? Why do they persist? It may be that they continue to confuse and generate revenue from the few Yahoo! users who remain. Another possibility, whether or not based in truth, is that these businesses being promoted no longer exist, yet their hordes of bots, let loose upon Yahoo! (which in the 2010s seemingly makes no business sense) continue to search for human users to visit their dead. It is as though they now seek their maker.

This is the result of the chatroom’s success –a bot-pocalypse, whereby individual humans have been extinguished from a social environment after its popularity. Bots, spam, scams follow success, and over-population in the past has led to a flight from the chaotic environment, to other social spaces, a result similar to what Virginia Heffernan describes as “suburbia” with respect to regulated app culture, but which could easily be applied to the flight from pre-web 2.0 social spaces to the structure of Facebook (or, more recently, from Myspace to Facebook).[4] The bots are all that’s left as proof of a social space’s former glory; picking apart what’s left of the chat carrion. Using auto-response, the bots are subject to well-defined algorithms, rules of sociality and expected reactions, even when no one is there. Where have all the humans migrated in the wake of this virus?

Not surprisingly, it is worth noting that a few in Yahoo! Chat lurk behind the horde, mostly a few males. They seek the token flesh-and-blood female. This is the result of a pathetic strategy; if it is only they and the bots, then the sole female is uncontested. This is the new standard of not only Yahoo! Chat, but others like Chat Avenue, whose adult (i.e., sex) room refreshes at such a rapid pace that conversation is made impossible. One-liners and introductions are all that remain as the majority male user sits back to compete for the rare, “amateur” female. Conversation is made only in private, one-2-one. The goal is no longer cybering (not to be confused with a sext in mobile culture), which has become insufficient; instead, it is the hunt for the human female, and the possible webcam to follow, which inspires the male user of these dead zones. Engaged in a complicated form of necrophilia, the user hopes to find a sex partner in a cemetery.

On Anonymity and Pseudonymity

“There are reasonable theories about what brings out the best or worst online behaviors: demographics, economics, child-rearing trends, perhaps even the average time of day of usage could play a role. My opinion, however, is that certain details in the design of the user interface experience of a website are the most important factors.”

-Jaron Lanier[5]

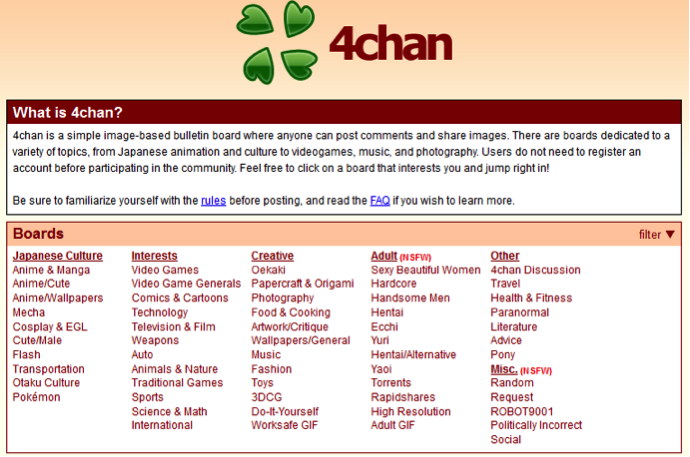

Although Zuckerbergian philosophy states that all should be shared,[6] anonymous is on the rise. In reaction to the over-publicity of the self (which one could argue is in itself violent and pornographic in its own self-serving way)[7] as conditioned by the social web, users have flocked to the other extreme of pure anonymity, preferring to live under the more anarchic conditions facilitated by 4chan for the sake of maintaining a level of power and control over their own privacy and identity. For these users 4chan is empowerment; 4chan is honest.

The architecture of a previous period fostered a certain behavior, in the form of pseudonymity, just as the current social web fosters publicity. But the differences can still be seen today, as Lanier explains:

Participants in Second Life (a virtual online world) are generally not quite as mean to one another as are people posting comments to Slashdot (a popular technology news site) or engaging in edit wars on Wikipedia, even though all allow pseudonyms. The difference might be that on Second Life the pseudonymous personality itself is highly valuable and requires a lot of work to create.[8]

A pseudonym especially represents an earlier Internet, where a chat handle was infused with identity. It is with this standard that I chose talking HEAD™ in the 1990s, with the trademark symbol giving me ownership to my handle when in my favorite social space, L.A. Live Chat. It was mine, it was me. This name soon had a history, it represented me as an individual, and it sometimes said more with one word or phrase about my likes and dislikes than any profile could. Anonymity existed then, but not as an identity or personality, but as a disguise to be mistrusted and sometimes feared. Anonymous was not respected, more reviled and ignored. It usually meant trouble.

The most recent form of pseudonym, which is found in one’s actual name as per social networks, is a strange case. Here lies yet another dynamic conflict of identity. The online offers the ability to shape one’s identity, separate from the actual day-to-day; an important distinction. Yet now we are asked to do the same as ourselves, with real friends and acquaintances. How one negotiates who they want to be with and who they are is a difficult game. Now, one is forced into publicizing all, defining identity by the number of friends, likes, reblogs, and activities (activism) –we must all act as our own PR agents, releasing press releases on our own behalf. This is the result of share-all philosophy, which paradoxically loses the individual in the process. The anxiety of the public is profoundly obvious with the extreme position played by social networks (public) and 4chan (private).

Enter: Stranger Chat

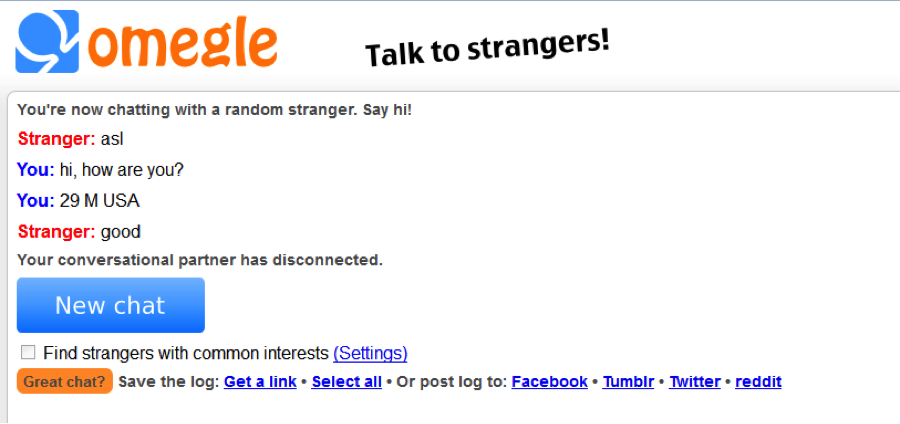

Like 4chan before both Omegle and Chatroulette are the creations of teenagers.[9] What makes these chatrooms representative of the anon-web is their emphasis on the “stranger” (hence their categorization as “stranger chats”). Rather than a virtual bar or room, one enters an environment more akin to a non-space, floating and unstable, conversations occur in the ether, spontaneously, uncontrollably. In a stranger chat, Omegle specifically, there are no chat handles, and no pseudonyms; there is only You and Stranger.

Strangers have the option to perform either text or video chats. Either way, upon entering, Strangers are thrust into a conversation with an anonymous other. “You’re now chatting with a random stranger. Say hi!” declares Omegle. A headline above reads, “Talk to strangers!” Here, the headline promotes the stranger, in a way which resembles an advertisement to see the two-headed boy or bearded woman, a dark-carnivalesque social environment, filled with sneaky, shameful eyes. To be strange and anonymous is unique, and freakish. Today it is as if the ability to meet someone outside one’s network never existed. We are condemned to know, or to be in the know. The online stranger is once again the new fetish, the new social high.

This is the standard experience of the teenage Poole, Leif K Brookes (Omegle) and Andrey Ternovskiy (Chatroulette), these children of the anon-meme. Their formative teenage years occurred at the opening wave of the social web, the success of MySpace and other social-networking websites, Wikipedia, Google, and high-speed expectations. They have no alternate experience of the WWW, of a web 1.0, and now not only do they long for the mysterious, the strange, and the anonymous in the age of Facebook, but they decide to create it.

The success of stranger chats lies mainly through the use of webcam by users. One agrees, by virtue of entering, to being thrust into a chat with one other (verifiably multiple in the case of video) with the decision to next or disconnect in order to spin-the-wheel and find a new stranger. Rather than text, the image now takes precedence in a stranger chat. It is an endless array of faces-in-render (the time it takes for a video to load), in which conditioned users can quickly spot male genitals before they are fully-rendered. The perpetual “nexting” resembles the reload or refresh of earlier chatrooms as one waits for the next post, next comment, and next face.

Gender is king; a/s/l (age, sex, location) or the image of the body is the deciding factor. This is unchanged from the earliest days of the Internet, chatrooms, and the use of webcams, and practice of camgirls. The practice of asl had disappeared until the return of the chatroom. The Omegle-male, like the lonely Yahoo! version, waits for the long-hair, the breasts, the “f” in “asl?”, and if “m” is the response, then quickly nexts. This if-then auto-response is a reminder of the bot, who like V’Ger, of Star Trek: The Motion Picture (Paramount, 1979) seeks its maker.[10] However, no longer must the male go through the longer procedure of sifting through sometimes hundreds of chat handles, since now, the conversation one-2-one or cam-2-cam (c2c) is part of the system.

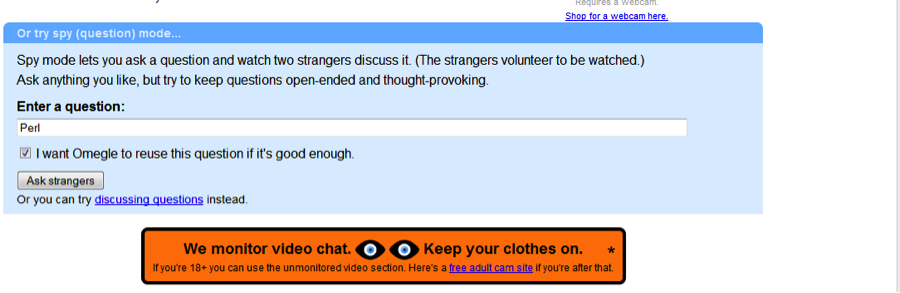

Omegle is the MySpace of stranger chats, which means Chatroulette is the Facebook. The former as of now refuses to clean up its act (besides an option to visit an adult website). Aside from a CAPTCHA, to identify humans, and a content warning, there is no spam reporting, and it continues to indulge in its anon-meme. Spy (question) mode is an option that allows a three-stranger Omegle text chat. Complicating this ménage à trois, however, is the role of Stranger #1: the one who initiates spy-mode must first choose their own question (as conversation starter). The initiator is then relegated to viewer, or voyeur. Seemingly powerful, instead one is immobile, unable to participate in the conversation. The initiator can only sit back and read as the conversation unfolds. At this point such confusion between passive and active should not be a surprise with respect to the anon-web and social web contradictions. So weak in fact is the initiator that if one of the two strangers disconnect from the chat, then the entire room is refreshed with two new strangers. Either the conversation succeeds or it continuously restarts. In spy-mode, we have a glorified, stylized, acceptable hacking (without needing any coding knowledge).

Chatroulette, on the other hand, is a pop culture hit. It has gone through various updates and changes in both form and content due to its success. While Omegle has remained something of a dirty secret, Chatroulette has been featured in mass media outlets, and myths of its use by the likes of pop star Justin Bieber, to name one, have made the rounds.[11] Each update to Chatroulette leads to a move away from pure stranger chat status and closer to a social web friendly chatroom. With an added profile option, and required login, one must provide information related to a/s/l as well as user names and email addresses. It is fitting that in Chatroulette one is labeled “partner” rather than “stranger.” Chatroulette is cleaning up, personalizing, and profiling. It is dipping into the meta-aggregation of selfdom. Inappropriate behavior may be reported and dealt with, and after multiple reports, one is banned and forced into community service if one wishes to return.[12] Chatroulette is seeking to be something more socially acceptable, modeled after a social web. Its future hinges on its integration with other applications, while this may also already portend its demise. On the other hand, Omegle, the “great zero,” remains the end-world, trash-heap, like MySpace before it.

The Dead Zone II: The Ballad of a Hanged-Man

“In the electric age we wear all mankind as our skin.”

-McLuhan

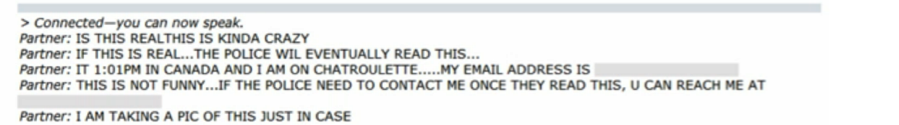

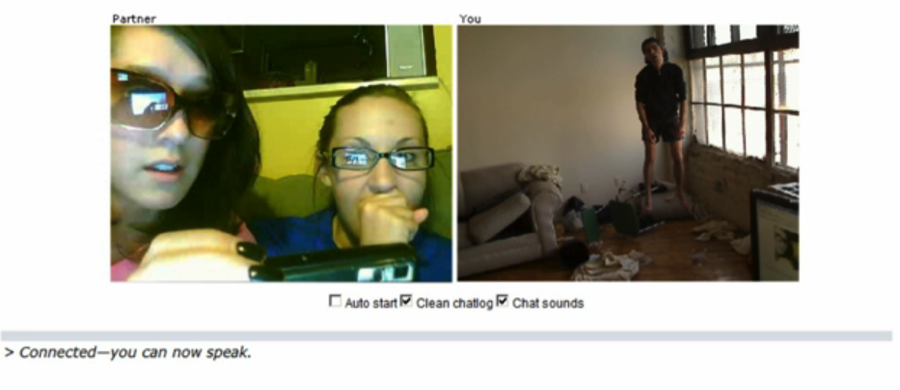

“It’s moving!” yells a Chatroulette user who has just encountered the webcam stream of an apparent suicide. The man is hanging, almost imperceptibly moving. The room is a mess, with the chair he stepped off of thrown to the ground. Then at the foreground, bottom right corner is the dead man’s laptop, with a partial view of a webpage –Chatroulette, transmitting an image of the other user, as they watch the dead live, mise en abyme.

It is curious that the user who screams in fear and who even goes so far as to call the authorities to report the suicide can use no better pronoun than “it” to describe the dead man. Does he believe it or not, or is it typical that the dead become a singular neuter pronoun even in the hypersexual Chatroulette? But, maybe the opposite is true. If in Chatroulette “faces and bodies become objects,” as Sherry Turkle claims, then the hanged-man may be the most human being nexted.[13]

This moment, recorded on Chatroulette, uploaded to YouTube and then subsequently banned, is the online performance No Fun (2010) by artist duo Eva and Franco Mattes,

aka 0100101110101101.ORG.[14] It features a hanging Franco playing the dead, and the recorded reactions of the partner(s) who display various reactions from laughter, to horror, and anger, to shooting-the-bird, to one overweight middle-aged man not confused enough to seemingly cease masturbating. Images of death in the digital or digital deaths, attempts of or performances of suicide via webcam are an old fear, having existed even in web 1.0.[15] Paul Virilio metaphorically anticipated this death of the private-public dichotomy with the search for specters haunting Houston’s apartment.[16] Now there are no ghosts, just friends.

In the Mattes’ representation of death, we have the next generation of the digital death scene. Whereas Virilio’s example describes a very clear distinction between the private real-space of a user compared to the public network that allows users to access Houston’s webcam, her self-surveillance, No Fun speaks to a loss of the online-offline distinction with regard to space. What the Mattes succeed at by virtue of upsetting the Chatrouletters is to reintroduce the other space. This could also be described in terms recognizable to the social web as the offline space (but it could be the difference between heaven and hell). Imagine the hypnotic drone, or the numbness of the nexting to be broken, indeed violently, by the image of the hanged-man, dangling in his room. It occurred to at least one user that it was real enough to try and describe to the authorities via mobile phone how Chatroulette works, and why he does not know where the hanged-man’s room is –a profound example of naiveté.

Imagine the user: suddenly, the person is in another, physical space, there is recognition of a (formerly) living, breathing, and flesh-and-blood human on the other side. We are not alone. Yet, most will click next, move on, and forget. It is easier to consider or want it to be a hoax, which it ultimately is. Is it the fear of death or the recognition of the other? Speaking of auto-amputation as we extend our bodies through an electric medium, McLuhan describes the numbing effect, or counter-irritant, resulting from the pressures of self-image extension. Narcissus mistook his own reflection or image for the other, and this “extension of himself by mirror numbed his perceptions until he became the servomechanism of his own extended or repeated image. The nymph Echo tried to win his love with fragments of his own speech, but in vain. He was numb. He had adapted to his extension of himself and had become a closed system.”[17]

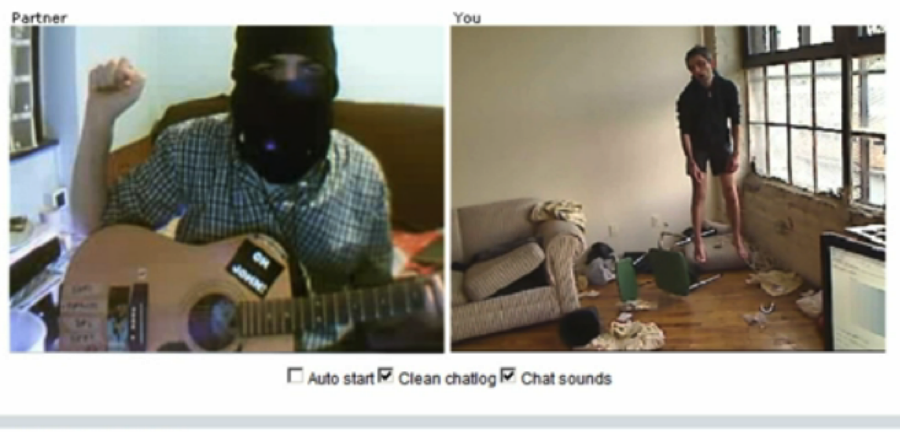

The video ends with a masked man equipped with an acoustic guitar. First, he performs the role of a Zapatista revolutionary; black masked, he holds his right fist up. Slowly, he acknowledges the death scene, and what else can he do but serenade the hanged-man. He begins strumming a heavily reverbed acoustic-electric, a sign-off to the offline, a dirge for the anonymous dead.

[2] Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media: The Extension of Man, (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1965), 5.

[3] McLuhan, 5-6.

[4] Heffernan writes, “This suburb is defined by apps from the glittering App Store: neat, cute homes far from the Web city center, out in pristine Applecrest Estates. In the migration of dissenters from the ‘open’ Web to pricey and secluded apps, we’re witnessing urban decentralization, suburbanization and the online equivalent of white flight.” “The Death of the Open Web,” New York Times, May 21, 2010, accessed March 7, 2013, http://www.nytimes.com/2010/05/23/magazine/23FOB-medium-t.html.

[5] Lanier, 62-3.

[6] Zuckerberg’s Law, “Y = C *2^X — Where X is time, Y is what you will be sharing and C is a constant.” Alexia Tsotsis, “Mark Zuckerberg Explains His Law of Social Sharing

,” Tech Crunch, July 6, 2011, accessed March 7, 2013, http://techcrunch.com/2011/07/06/mark-zuckerberg-explains-his-law-of-social-sharing-video/.

[7] Baudrillard writes, “…today there is a pornography of information and communication, a pornography of circuits and networks, of functions and objects in their legibility, availability, regulation, forced signification, capacity to perform, connection, polyvalence, their free expression…” The Ectasy of Communication, (New York: Semiotext(e), 1988) 22.

[8] Lanier, 63.

[9] Then 18-year-old Leif K-Brooks of Brattleboro, Vermont created Omegle, which launched on March 2009. The creator of Chatroulette is then 17-year-old Andrey Ternovskiy of Moscow, Russia. The site launched in November of 2009.

[10] The film, directed by Robert Wise, features an antagonist named V’Ger, a living-machine. The spoiler: it is discovered that V’Ger is a lost Voyager 6 probe, which traveled far, gathering so much knowledge and an upgrade by another alien race, which leads to the development of consciousness. It seeks an end to its search, the transmission of data collected through its travels, and the merging with its Maker, a human-being.

[11] The Daily Show with Jon Stewart, March 4, 2010, accessed March 7, 2013, http://www.thedailyshow.com/watch/thu-march-4-2010/tech-talch—chatroulette.

[12] Andrey Ternovskiy explains: “To me, it’s like the street in some big city, where you see all kinds of unknown faces. Some of those faces appeal to you, some disgust you. Chatroulette is a street that you walk along where you can chat to whomever you like. The program makes the Internet more like real life. As for the ‘freaks and fuckers,’ I’m working on a solution. I have integrated a ‘report’ function into Chatroulette. If three users complain about the same bum, then that user is automatically banned from using the system. So there are a lot less of them already.” Read, “17-Year-Old Chatroulette Founder: ‘Mom, Dad, the Site Is Expanding’,” Spiegel Online, March 5, 2010, accessed March 7, 2013, http://www.spiegel.de/international/zeitgeist/0,1518,681817,00.html.

[13] Sherry Turkle, Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other, (New York: Basic Books, 2011) 225.

[14] The video can be found at the artists’ homepage, http://www.0100101110101101.org/home/nofun/index.html.

[15] Counter culture guru Timothy Leary, dying of terminal cancer in the mid-1990s, considered broadcasting his suicide online. A New York Times article reports, “The Web, in fact, relies on the breakdown of bounds between private and public; it creates a sense of a large community as well as absolute isolation. The public and private realms become illusions: there is no guaranteed community and no real privacy. One site lists ‘ill celebrities,’ with details of critical illnesses (http://www.tiac.net/users/efoley). Everywhere we are told more than we want to know. ‘Suicide’ bulletin boards for teen-agers on America Online broadcast troubled graffiti to millions: ‘Hey i’m 15 a month ago i almost killed myself I took tons of pills and when that didn’t work i slit my wrists. God why didn’t i die?’” Edward Rothstein, April 29, 1996, accessed March 7, 2013, http://www.nytimes.com/1996/04/29/business/technology-connections-web-tuning-timothy-leary-s-last-trip-live-his-deathbed.html.

[16] Paul Virilio, The Information Bomb, translated by Chris Turner, (New York: Verso, 2005).

[17] McLuhan, 41.