“These creatures are nothing but pure motorized instinct. We must not be lulled by the concept of these are family members or friends. They are not.”

– Eye-Patch Wearing Scientist[1]

Prologue: Unfriending the Undead

A year ago I unfriended my dead cousin.

A few days following her birthday her Facebook profile photo changed to mark the occasion. The cropped photo was from an older family portrait. She looked young and alive. She had died the previous year, yet her profile remained updated by posts from family and friends in remembrance of their loved one. Even strikingly private changes continued to occur, like those updates which only the owner of said profile might do. Therefore, I write “had died.” My cousin remains online, connected, friended, communicated with, updated, written to in the present-tense, past-tense, and future-tense, as in when-we-meet-again. She is “live.” Someone is acting as her moderator, or mod; her mediator, or medium.

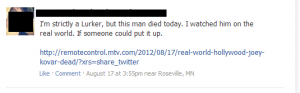

I unfriended my cousin not out of dislike, but out of an intuitive distrust of the process and system which keeps her a living-dead user, and the strange conflation of public-private space affecting both states of her being. The ethics of moderating social memorials and how easily social web users participate is problematic and worth investigating,[2] especially since they do not critically examine social changes. Death 2.0 is a perpetual social eternity. I see the heartbreaking posts of those communicating with the one they miss, and those who lurk and read them—those death voyeurs—and I am interested in what this process means for both the living and the dead.

I begin with a deeply personal experience because I want to speak as a living being referring to the dead—what it means to live with technology, with the non-sentient, and with the use of our image, and our identity by other systems, people, and things. I am personally invested; I am personally embedded. I will make a connection here to three ancient archetypes transfigured through popular cinema: the ghost, the cannibal, and the zombie. Their emergence, or reemergence, with respect to communicative and entertainment media technology illustrates the state-of-the-user or audience today with respect to life and death in a technological culture.

A few things are happening simultaneously. In 2010 Wired Magazine declared the [link no longer active][3] a brazen declaration that Wired is no stranger to issuing,[4] but in this case the dramatics of selling a magazine may be secondary to facts. Ironically, the success of the Tim Berners-Lee’s World Wide Web, i.e. everyone’s need to always be connected, has aided in the explosive growth of mobile computing, which is not always web based.[5] It is a “machine-to-machine future…less about browsing and more about getting,”[6] and therefore, consuming.

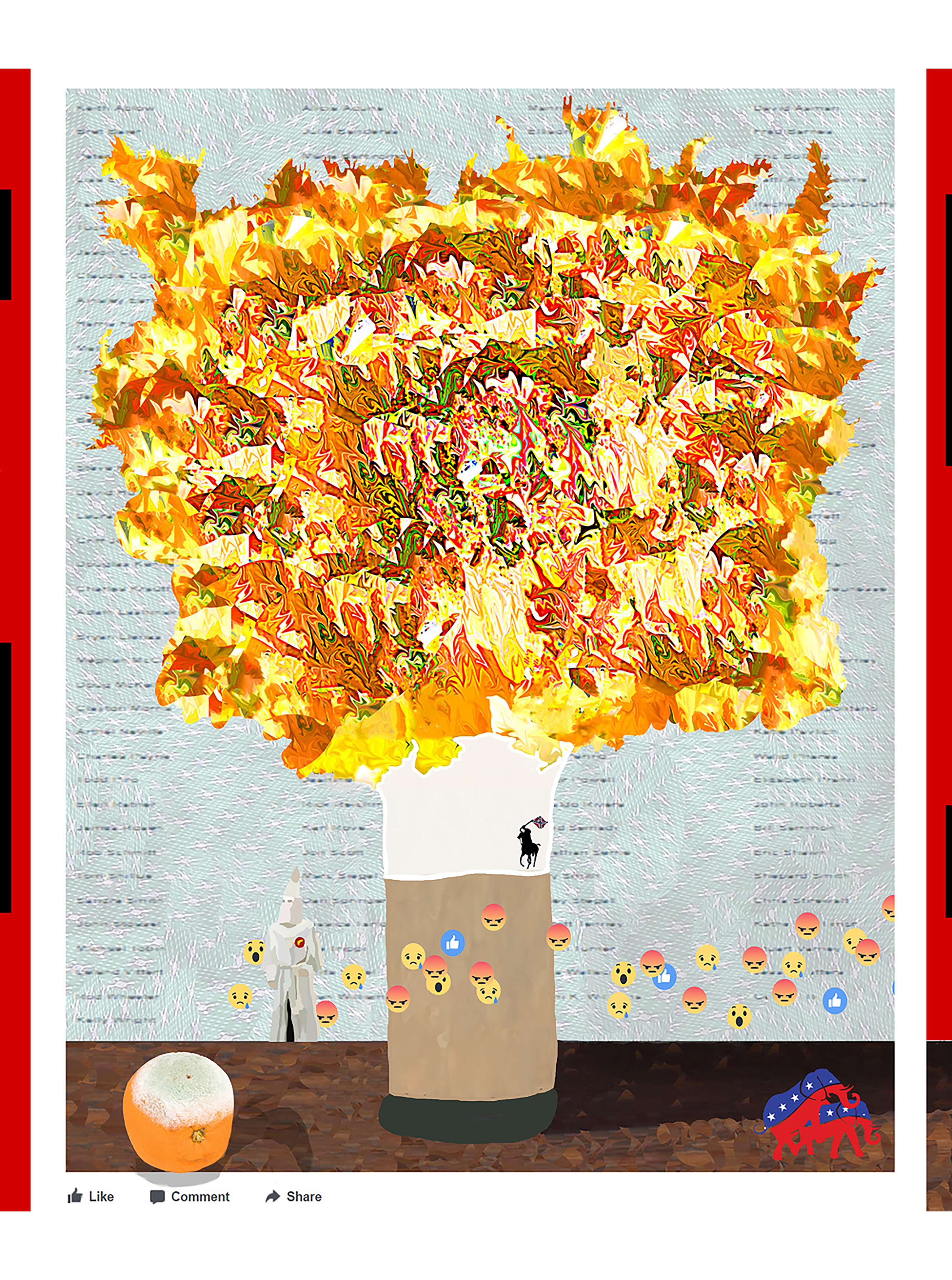

Surfing is obsolete, and cyberspace is gone. There is no time to enmesh oneself in a new-space when real-space beckons.[7] Instead, the network communities grow, inspired by social network standards, architecture, and expectations. Homepages have transformed, chat rooms no longer dominate, and social network profiles representing the “real you” rather than the “avatar” succeed in their place.[8] We navigate through quick hyper jumps between apps rather than HTML hyperlinks. We look up and down from our mobile phones in rapid succession to the traffic around us as we drive. During the development of this network and its standards, social practices, and communities, there emerges a tension between the online and the offline and, subsequently, between life and death. The reemergence of the zombie in media is but a result of this tension.

Zombie Popocalypse

While the pop-zombie of the 1960s never disappeared, the beginning of the 21st century that has brought an endless assortment of media surrounding the zombie has proliferated for very different reasons. Most notably is the meme of the zombie apocalypse, consisting usually of how-to survival guides and trusty handbooks in preparation for the end-times.[9] Even the Center for Disease Control (CDC), playing on the meme, issued a “Social Media Preparedness 101: Zombie Apocalypse” [link no longer accessible] on their official website. The CDC also produced what they call a Zombie Novella, or digital comic described as:

A fun new way of teaching the importance of emergency preparedness. Our new graphic novel, ‘Preparedness 101: Zombie Pandemic’ demonstrates the importance of being prepared in an entertaining way that people of all ages will enjoy. Readers follow Todd, Julie, and their dog Max as a strange new disease begins spreading, turning ordinary people into zombies.[10]

Besides the deluge of zombie films, cell phone commercials, literature, zombie walks and meet-ups, even academia is getting in on the plague with one group releasing, “When Zombies Attack!: Mathematical Modeling of an Outbreak of Zombie Infection.”[11] The study ends with what we already know:

In summary, a zombie outbreak is likely to lead to the collapse of civilization, unless it is dealt with quickly. While aggressive quarantine may contain the epidemic, or a cure may lead to coexistence of humans and zombies, the most effective way to contain the rise of the undead is to hit hard and hit often. As seen in the movies, it is imperative that zombies are dealt with quickly, or else we are all in a great deal of trouble.[12]

What has reawakened the zombie? What is it with this new eschatology of the walking dead, and why is it happily spread by our new mobile media situation?

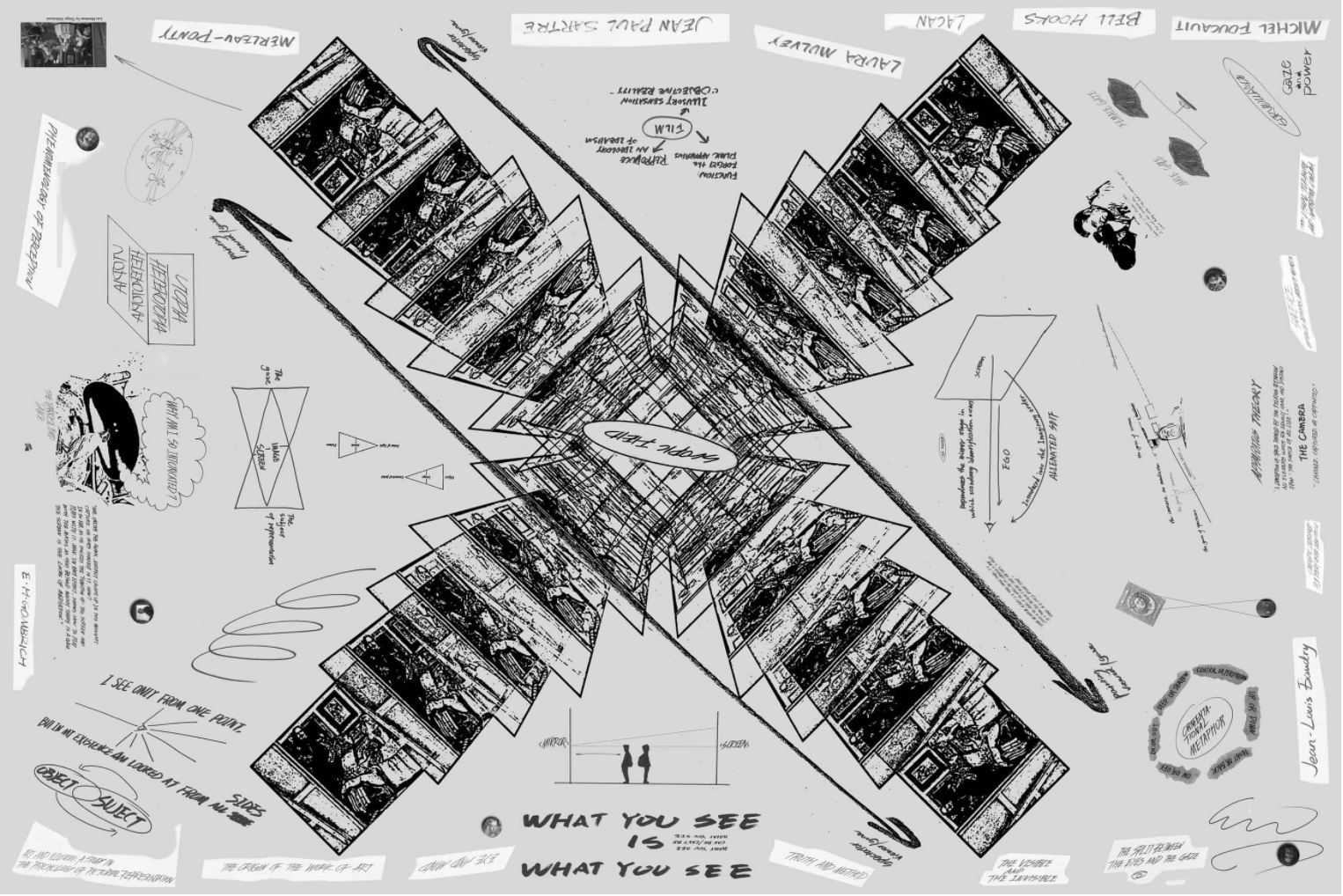

The Disappearance of Spirits

The ghost-in-the-machine is an old specter haunting users of communication technology. In the nineteenth-century the expansive wires of the telegraph transmitted messages from the afterlife, and the television of the twentieth-century stained monitors with images of the dead, both audibly and visually.[13] Partly what fascinates users is the capturing of another person through a recording, a historical archiving of the voice, the image, and or the moving picture. The idea of the perpetuation of what is gone, even if it’s just for a moment, is comforting. Past persists vis-à-vis its recording, its cataloging, tagging, dissemination, sharing, and archiving. Everyone is potentially forever-available.[14] One might say we are allowed the possibility of ownership of one another; it is an answer to the crisis of death, of loss (including memory), and of nothingness.

Ghosts are neither here nor there. They are immaterial. They are that thing which survived the death of the body, yet they allude to it and often represent lost souls forever trapped in the material world. They “missed out,” tortured to forever remember the body they were once a part of. A medium offers to bridge the communicative gap in order to allow the living and ghosts to speak with their lost friends, lovers, parents, siblings, or strangers. Even if the ghosts are strangers, they are still familiar as humans, or former humans.

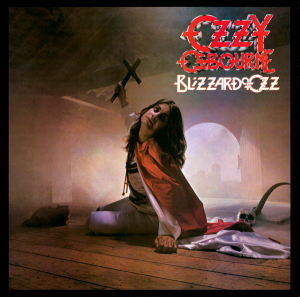

Dark spirits, or poltergeists, also haunt media: The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (Capitol, 1967) contains secret messages and codes, while the playing of an Ozzy Osbourne record is powerful enough to possess a youth to commit suicide.[15] Oddly, the process of playing songs at varying speeds, forwards and backwards, in an effort to glean coded messages is lost on the CD and the mp3 era when the remixing and deconstructing of popular music is arguably the easiest it has ever been. There isn’t even time for mysticism anymore.

Ghosts are exorcised. We’ve moved on. The setup for this change is partly the use of wireless technology and the paradoxical result of the shifting terrain of private-public space. As Jeffrey Sconce writes with regard to the introduction of wireless communication technology:

Whereas the ‘live’ qualities of electronic transmission in telegraphy and telephony had put the listener in immediate, fairly intimate, and ultimately physical contact via a wire with another interlocutor across time and space, wireless offered the potentially more unsettling phenomenon of distant yet instantaneous communication through the open air… communal yet diffuse, isolated, and atomized…[16]

With this voyeurism, tele-surveillance takes on a new meaning. It is no longer a question of forearming oneself against an interloper with criminal intent, but of sharing one’s anxieties, one’s obsessive fears with a whole network, through over-exposure of a living space.[19]

Tele-vision is thus active rather than passive[20] (though the passivity of traditional television is in question). It works by “exposing and invading individuals’ domestic space,” and due to “ ‘real-time’ illumination, the space-time of everyone’s apartment becomes potentially connected to all others, the fear of exposing one’s private life gives way to desire to over-expose it to everyone, to the point where, for June Houston, the arrival of ‘ghosts’…is merely the pretext for the invasion of her dwelling by the ‘virtual community’…”.[21] The result is a new localness, or what Virilio calls social tele-localness. Today this is called social media, an outgrowth of a Web 2.0 ideology.[22]

Virilio is writing in 1997-98, during the success of early web browsers. At that time live streaming public cams were new enough for critics and the public to contend with. Thus, Houston serves as a transitional character in the shape of social tele-localness. Houston did not have to go online. She did not have to install webcams and invite the strangers in. This is a nascent example of present self-surveillance and personal overexposure, which at its extreme results in geo-social networking like FourSquare’s location check-in.

Houston was free to choose, but at the time of her experiment, the possibilities were just specters, or pure potentiality. We exude it now, and although the ideology of Web 2.0 declares infinite choice and interactivity, with it comes the unbearable social pressure to sign up and share. The feeling of melancholy and a paradoxical neither-here-nor-there anxiety during the early use of wireless networks has resulted in our present excessive self-publicity and a transformation of Houston’s former “strangers” into our “friends.”

The Information Bomb is prescient and makes more sense in our social web where the fluidity between the online and the offline essentially declares the end to an already problematic binary. In this state, the natural world is negatively associated with the term “off” as opposed to “on,” dark versus light, dead versus alive. We are not concerned with the possibility of poltergeists any longer, with blurry wandering, invisible eyes. Social tele-localness is our state. Our real friends are also our numbered friends, and their avatars and digital identities are supposedly theirs. We know them as beings with bodies, affecting actual space; therefore, we are subject to the unbearable state of being perpetually in-the-know. Like our dead, we are not allowed to forget, or to have a memory-of, and acquaintances, friends, and enemies become harder to define, or delete.

Something else has taken the place of the ghosts: our friends.

From Cannibalism to new-Zombiism

In Miami in May of 2012, Rudy Eugene attacked and began to cannibalize the face of homeless man Ronald Poppo in broad daylight. Eugene was shot and killed by an officer, while Poppo lived through the ordeal, though severely disfigured, and essentially faceless. The reasons for Eugene’s behavior remain unknown. The media quickly dubbed the attacker both the “Miami Zombie” and the “Causeway Cannibal.”[23] Sometimes, Eugene is simultaneously referred to as a zombie and a cannibal in a single article,[24] but logic dictates that Eugene cannot be both.[25] All signs point to him acting unlike himself, hence a zombie, yet he most certainly was not the undead. Therefore, he must be a cannibal.[26]

In May of the same year, a video titled 1 Lunatic 1 Ice Pick was posted online, featuring the stabbing, dismemberment, and murder of a man named Lin Jun, followed by acts of necrophilia and cannibalism. The video was preceded by a social media promotional campaign created by the killer days before the incident.[27] The aforementioned video was posted on a Canadian shock-site called BestGore, which in the past has received as many as 15 million page views per month. While on the run, the suspect, Luka Magnotta, was apprehended in Berlin while reading news stories about himself in an Internet café.[28] Luka was a heavy user of social media, and prior to the murder he was suspected of posting YouTube videos featuring the gruesome murder of kittens.[29] He currently awaits trial.[30]

In 1980 the film Cannibal Holocaust (Grindhouse) was released. Known today as a cult-gore classic, or “The One That Goes All The Way”, the film, directed by Italian filmmaker Ruggero Deodato, is the most well-known in a series of cannibal exploitation films during a period called cannibal boom. The tropes are similar: white European travelers visit the Amazon and encounter cannibals, who are either untouched and “primitive” in their ways or driven to viciousness by the “enlightened” westerners. By the standards of 1980’s shock, Deodato’s film is known for its realistic use of gore and impalement, but Cannibal Holocaust is also a work of criticism. It follows bloodthirsty western documentarians who are soon found guilty of staging violence for their cameras, driving the natives to attack, and forcing the audience to wonder who the savages really are. Filmed in a pseudo-documentary, cinéma vérité style, Deodato attempts to make the consumer a participant in the media-gore.

Seen in total, the cannibal boom era is interested in the “other” in film, mass-media exploitation, consumption, the rational, and the savage. Humanity is questioned, or differentiated. Deodato criticizes the cannibalizing powers of media and network television that exploit the horrors, the gore, and violence of the civilized, or socialized, world. Beginning with Italian mondo-films of the 1960s, like Mondo Cane (Cineriz, 1962),[31] this pseudo-documentary style shocks the viewer, and it is the logical precedent to Faces of Death (Aquarius, 1978),[32] and today’s very real Bestgore.com, who are too impatient to stage death.

On the other hand, the pop-zombies I have been referring to are made famous by filmmaker George A. Romero, beginning with Night of the Living Dead (1968). Various explanations are given to the origin of these zombies, none of which is voodoo, i.e. the classical zombie. Instead, germ warfare, or accidents in science, has spread what has come to be known as the zombie plague. Zombies are the dead, whose lifeless corpses somehow walk again, but devoid of their personality and memory, other than an innate need to feed, a hunger for the flesh of living humans.[33] Romero’s early trilogy, ’68, ’78, and ’85[34] periodize their messaging, from racism, to consumerism, and the military-industrial complex. They are a warning of what humans are becoming.

What are we becoming? Surely not the cannibal since it refers to the “other” in a way that invites the character of the unknown stranger. We are not strangers; we are all friends. Instead, the zombie plagues the network, part body part germ-warfare, machine-like in its programming, it shares its brand of information, and it does so as a recognizable body, albeit undead. It could be a family member, brother or sister, friend, or enemy –they are all the same now. It is familiar in how it shares, like an online public profile, spread too wide and too deep. It is forced to forever walk with nothing but a burning hunger to feed and share.

In that case, who really is dead my cousin or me?

Epilogue: MyDeathSpace, New-Zombiism & Network Tele-vision

Myspace, the first successful social network[35] of the social web, persists but as something closer to a monument to the living dead –pure nostalgia and already retrofied.[36] It is but a shell of its former glory, though it remains in the network, live. Its standards, community and vernaculars helped influence Facebook’s current glory.[37] The icon of your first friend, Tom,[38] is but a digital death mask that persists today. Myspace’s success resulted in MyDeathSpace.com,[39] an online obituary of those social networkers who have died. On the website, a blurb is posted explaining an individual’s demise, followed by a link to their social media profiles. The “My_Space” of MyDeathSpace is no longer a reference to only those dead on the former social network of choice, but to all those dead in network-space. MyDeathSpace has since adapted, and followed the living and the dead to the successful Facebook. Social networks come and go, but death is immortal.

Virilio writes:

To prefer the illusions of networks – drawing on the absolute speed of electronic impulses, which give, or claim to give, instantaneously what time accords only gradually – means not only making light of geographical dimensions, as the acceleration of rapid vehicles has been doing for more than a century now, but, above all, hiding the future in the ultra-short time-span of telematics ‘live transmission’. It means making the future no longer appear to exist by having it happen now. No future…[40]

Welsh artist Rhys Himsworth’s installation New Life (2008), consists of a cardiograph and laptop reprogrammed to gather data from MyDeathSpace which allows the cardiograph to print images of the dead. The cardiograph paper print-out steadily builds throughout the installation, folds and folds gather along the floor, filling whatever space it is currently housed in. Ironically, it is as if even Himsworth’s attempt at infusing new life into the digital dead instead results in an even more clinical, cold, and technological representation. The artist uses old-media, black on white print technology in an art gallery, a closed-in institution, to honor or exploit the dead. The cardiograph monitors the state-of-the-network. Left alone in a gallery, it expels the faces of the living-dead, who in an act of inversion now appear more real online.

-

- A summary of Douglas Rushkoff’s book titled “Present Shock,” which argues that the speed in which the world is changing is making us lose the ability to cope.

- Digital funerals, for real-life deaths.

- Who has legal access to your digital identity once you die?

[1] Unknown scientist debating on television post-zombie apocalypse. He says, “The normal question, the first question is always, are these cannibals. No they are not cannibals. Cannibalism in the true sense of the word implies an interspecies activity. These creatures cannot be considered human. They prey on humans. They do not prey on each other. That’s the difference. They attack and they feed only on warm flesh. Intelligence? Seemingly little or no reasoning power. But basic skills remain of more remembered behaviors from normal life… I might point out to you that even animals will adopt basic use of tools in this manner. These creatures are nothing but pure motorized instinct. We must not be lulled by the concept of these are family members or friends. They are not. They will not respond to these emotions.” Dawn of the Dead, directed by George A. Romero (1978; Laurel Group Inc. /United Film).

[2] “After Death, Protecting Your ‘Digital After-life,’” NPR, January 10, 2011, http://n.pr/i7Qtp5 [Editor’s note: Article no longer available]. Also, the story of e-mails being sent from a dead man’s account and how you too can set this up, “Emails sent from dead man’s account helping family and friends find closure,” Yahoo! News, March 14,2012, http://yhoo.it/A4Gqis [Editor’s note: Article no longer available]. There one can find links to Digital Beyond, who offers after-life digital services. Visit, http://www.thedigitalbeyond.com/.

[3] Chris Anderson, “The Web Is Dead. Long Live the Internet,” Wired, August 2010, [link no longer active].

[4] Kevin Kelly & Gary Wolf, “Push!,” Wired, March 1997, http://www.wired.com/wired/archive/5.03/ff_push.html.

[5] Jeremy Vanderlan, “Mobile Internet Use Surpassing Desktop Internet Use by 2014,” Aids (blog), October 11, 2011, http://blog.aids.gov/2011/10/mobile-internet-use-surpassing-desktop-internet-use-by-2014.html.

[6] Anderson.

[7] Anderson explains, “Today the content you see in your browser — largely HTML data delivered via the http protocol on port 80 — accounts for less than a quarter of the traffic on the Internet … and it’s shrinking. The applications that account for more of the Internet’s traffic include peer-to-peer file transfers, email, company VPNs, the machine-to-machine communications of APIs, Skype calls,World of Warcraft and other online games, Xbox Live, iTunes, voice-over-IP phones, iChat, and Netflix movie streaming. Many of the newer Net applications are closed, often proprietary, networks.” The Pew Internet & American Life Project presents a more balanced view of the future of the Web and mobile-alternative uses. They summarize: “The Web Is Dead? No. Experts expect apps and the Web to converge in the cloud; but many worry that simplicity for users will come at a price.” And, “Many anonymous responders challenged the structure of the apps-Web question. Among their arguments: The world ahead is not either apps or the Web. A more hybrid world is likely. Moreover, the tussle between controlled content and user experiences on the one hand and openness on the other hand will play out in other ways.” Janna Anderson and Lee Rainie, “The Future of Apps and Web,” Pew Internet, March 23, 2013, http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2012/Future-of-Apps-and-Web/Overview.aspx.

[8] More problematically is the possibility that the “real you” is the new-avatar, with fantasy and reality mixing.

[9] See Max Brooks, The Zombie Survival Guide: Complete Protection from the Living Dead, (New York: Three Rivers Press, 2003).

[10] “Social Media:Preparedness 101: Zombie Apocalypse,” Centers for Disease Control and Preventions, July 16, 2012, http://www.bt.cdc.gov/socialmedia/zombies.asp.

[11] “When Zombies Attack!: Mathematical Modelling of an Outbreak of Zombie Infection”, by Philip Munz, Ioan Hudea, Joe Imad and Robert J. Smith?. In Infectious Disease Modelling Research Progress, eds. J.M. Tchuenche and C. Chiyaka, Nova Science Publishers, Inc. pp. 133–150, 2009, www.mathstat.uottawa.ca/~rsmith/Zombies.pdf.

[12] 146.

[13] As Jeffrey Sconce writes, “Telegraph lines carried human messages from city to cot and from continent to continent, but more important, they appeared to carry the animating ‘spark’ of consciousness itself beyond the confines of the physical body.” Haunted Media: Electronic Presence from Telegraphy to Television, (Durham: Duke, 2000), 7.

[14] Jonathan Sterne writes, “Although it is perhaps most pronounced in phonography, death is everywhere among the living in early discussions of sound’s reproducibility. The spirit world is alive and well in telephony and radio…The logic is impeccable –if sound reproduction simply stratifies vibration in new ways, if we learn to ‘hear’ other areas of the vibrating world, then it would only make sense that we might pick up the voices of the dead.” The Audible Past: Cultural Origins of Sound Reproduction, (Durham: Duke, 2005), 289.

[14] Jonathan Sterne writes, “Although it is perhaps most pronounced in phonography, death is everywhere among the living in early discussions of sound’s reproducibility. The spirit world is alive and well in telephony and radio…The logic is impeccable –if sound reproduction simply stratifies vibration in new ways, if we learn to ‘hear’ other areas of the vibrating world, then it would only make sense that we might pick up the voices of the dead.” The Audible Past: Cultural Origins of Sound Reproduction, (Durham: Duke, 2005), 289.[15] Osbourne was sued in 1986 by the parents of John McCollum, a teen who committed suicide. McCollum’s parents argued that it was Osbourne’s song lyrics for “Suicide Solution” which led to the teen’s untimely death. The successful album Blizzard of Ozz (Epic, 1980) is also famous for containing the song devoted to occultist Mr. Crowley.

[16] Sconce, 62-3.

[17] The website is archived by Wayback Machine, February 3, 1999, http://bit.ly/1b5gIpX, and for press on Houston, visit, http://www.flyvision.org/june_houston/pub/index.html.

[18] In an FAQ Houston is asked, “Is the GhostWatcher all just about art or is it for real?” She answers, “What do you mean ‘JUST about art?’ Are you saying art’s not for real? Can’t it be both? If I told you it’s this or that would it change anything? What part of this stream of bits (I mean the Web) can you trust?” May 4, 1999, http://bit.ly/S7KsqA.

[19] Paul Virilio, The Information Bomb, (New York: Verso, 2005), 58-9.

[20] Virilio is most likely focusing on the unquestionable interactivity of this new tele-vision, which offers content creation, for example, as well as the development of personal broadcasts, or “networks.”

[21] Virilio, 59.

[22] Tim O’Reilly breaks down Web 2.0 as: the web as a platform, crowd wisdom and content-creation heavy, perpetual beta, among other characteristics. “What is Web 2.0?” O’Reilly, September 30, 2005, http://oreilly.com/web2/archive/what-is-web-20.html

[23] Named for the Miami MacArthur Causeway where the attack took place.

[24] One headline reads, “Friends of cannibal Rudy Eugene say he was not ‘a face-eating zombie monster’ as police reveal first picture of homeless victim in bizarre Miami attack,” Herald Sun, May 30, 2012, and another, “Ronald Poppo Named As ‘Zombie’ Rudy Eugene’s Miami Cannibal Attack Victim,” International Business Times, May 30, 2012. Visit, http://bit.ly/KbpENz [Editor’s note: Page no longer available] and http://bit.ly/NbZrfa.

[25] Similarly, how can one be “un-dead” and yet not “alive”?

[26] Almost exactly a year later, Poppo continues to recover, amazingly staying positive throughout the ordeal, even recently recording a YouTube video thanking his donors and supporters, “Ronald Poppo, face-chewing victim, still recovering one-year later:Hospital,” CBS News, May 21,2013, http://cbsn.ws/1gQieK3.

[27] Glen McGregor, “References to snuff video made online10 days before suspected date of slaying,” The Ottawa Citizen, June 1, 2012, http://bit.ly/PZWdPF [link no longer active].

[28] Allan Hall, “Fugitive ‘cannibal’ porn star arrested in Berlin internet café…looking at news stories about himself,” Daily Mail Online, June 4,2012, http://bit.ly/KZOP29.

[29] Tristen Hopper, “Luka Rocca Magnotta hunted by online sleuths over kitten videos long before murder accusations,” National Post, January 6, 2012, http://natpo.st/LknwOY [Editor’s note: Page no longer available].

[30] Some things never change. The Daily Mail Online reports that Magnotta, like infamous killers before, receives and responds to fan mail while in jail, “Cannibal killer Luka Magnotta sets up special fan site so admires can send him letters in jail cell as he awaits trial for dismembering and eating his lover,” August 15, 2013, http://dailym.ai/1aZqc2y.

[31] Directors Paola Cavala, Franco Prosperi, & Gualtiero Jacopetti.

[32] Director Conan LeCilaire, aka John Alan Schwartz

[33] This is not entirely true to Romero’s zombies. Beginning with the famous intro cemetery scene in Night of the Living Dead (1968; Image Ten and The Walter Reade Organization), we quickly notice that the zombie is intelligent enough to pick up a rock and break a car window. Later, Dawn of the Dead refers to the routine of mall-shopping remains, and Day of the Dead’s *1985; Dead Films Inc and United Film Distribution) Bub not only remembers how to shoot a pistol, but dramatically chases and helps murder the antagonist (a living military member).

[34] In this order, Night of the Living Dead, Dawn of the Dead, Day of the Dead.

[35] Pete Cashmore, “Myspace, America’s Number One,” Mashable, July 11, 2006, http://mashable.com/2006/07/11/Myspace-americas-number-one/.

[36] Performer Justin Timberlake is now a co-owner.

[37] Myspace succeeded in creating the current comfortable form of the “friends list,” and “friend feed” as a bulletin board, the share, and the ability to make news and be news both on and offline.

[38] Tom Anderson is the co-founder of Myspace (2003), along with Chris DeWolfe. Tom was the default friend on Myspace for new users. He was your first-friend. His default icon, featuring his white shirt, will never be forgotten. He has since left Myspace and even joined Facebook. A 2010 Associated Press story explains: “And in a change that symbolizes it is really putting its past behind it, Myspace co-founder Tom Anderson, a smiling guy looking back across his white T-shirt, recently stopped being every new user’s first friend. Since last month, he’s been replaced by a cleverly named profile, Today On Myspace (T.O.M.), which features new songs, movie clips and celebrity updates and starts feeding into the new users’ stream right away. That leaves new users with a better sense of what Myspace has to offer, rather than leaving them with one friend and clueless, Jones said.” http://buswk.co/QwFUao

[39] Launched 2006

[40] Virilio, 94, author’s emphasis.