Last Friday, British Prime Minister David Cameron sat with President Barack Obama in Washington, D.C. to discuss a number of topics, including the recent attacks in France and the need to beef up anti-terrorism tactics.

Okay, cool. That’s a topic that should be discussed. What else was said and discussed during his visit?

BBC: “‘We face a poisonous and fanatical ideology that wants to pervert one of the world’s major religions, Islam, and create conflict, terror and death,’” said Cameron. “‘With our allies we will confront it wherever it appears.’”

Me: Cool. I agree with that.

BBC: “[Cameron] warned that the fight against terrorism ‘is going to be a long, patient and hard struggle’ but added that he was ‘quite convinced we will overcome it.’”

Me: Yep, yep, two thumbs up from me.

The Guardian: “A rolling program of transatlantic cyber ‘war games’ are to be conducted by British and US intelligence agencies to test their resilience in the face of mounting global cyber-attacks…a simulated attack will be targeted later in the year at banks in the City of London and Wall Street…”

Me: Cool! “Cyber War Games” sounds like a movie just begging to be made, albeit with a catchier title.

The NYT: “Cameron said, ‘The attacks in Paris demonstrated the scale of the threat that we face and the need to have robust powers through our intelligence and security agencies in order to keep our people safe.’”

Me: Okay, that sounds a bit ominous and could potentially lead to dangerous or reactionary solutions, but the threat is there and we must be able to detect it. Any other thoughts, Mr. Cameron?

The WSJ: “‘Are we going to allow a means of communications which it simply isn’t possible to read?’ Mr. Cameron said in a speech Monday. ‘No. We must not.’”

Me: Wait…wait wait wait wait wait. Oh, Mr. Cameron, you should have stopped while you were ahead.

David Cameron’s remarks on Internet security have come under fire from tech enthusiasts and security specialists who argue that the PM’s technological illiteracy and paranoia regarding encryption will lead to a dark future for both online anonymity and the safety of our digital identities. In a recent article on The Guardian’s website, independent computer security expert Graham Cluley said that the proposal to try and shackle encryption technology is “crazy…Cameron is living in cloud cuckoo land if he thinks that this is a sensible idea, and no it wouldn’t be possible to implement properly.”

The remarks reveal a dangerous side effect of the recent attacks in Paris. Sure, people may be out in the streets in solidarity with journalists and cartoonists and those who use their pens and their words to engage in social criticism, but there are also those who, like Mr. Cameron, will undoubtedly try to use the attacks as an example that supports their own agendas. I am not excusing President Obama, either. He has recently gone on record (with Mr. Cameron at his side) arguing in favor of stronger cooperation between the United States government and companies like Google, Facebook, and the plethora of messaging applications available to users that support encryption technologies. “If we find evidence of a terrorist plot…and despite having a phone number, despite having a social media address or email address, we can’t penetrate that, that’s a problem,” Obama said.”

If the leaders of two of the most powerful nations in the world are claiming that the act of encrypting communication technologies is essentially a danger to national security and a technique that evildoers can exploit to their advantage, what is the point of encryption in the first place? After all, you and I have nothing to hide…right? Right?

Wrong. Remember whistleblower Edward Snowden and the NSA documents he leaked to the press? Remember the NSA’s draconian surveillance techniques that were suddenly exposed for the world to see, including an interesting little program called PRISM? In the wake of these revelations, I frequently read (and heard) people try to downplay their tactics to argue in favor of “national security,” frequently citing the lack of “things” they felt the need to hide and the fact that the NSA would never need or want to target them for surveillance. But having a good grasp of why Internet security is so important to even the most basic of users is not just something that tin foil hat-wearers need to worry about.

I had a real laugh last week when I read that Gustav Nipe, chairman of the youth wing of the Swedish Pirate Party, fooled attendees at a major Swedish security and defense conference into connecting to an open Wi-Fi network that he himself controlled. Notice that I didn’t use the word “tricked,” because all he really did was create the network and watch as “…around 100 politicians, military officers and journalists logged into a network called ‘Open Guest’ and proceeded to search for various non-work-related things including ‘forest hikes’ and monitor eBay auctions.”

I simply don’t think that the average user is aware of how important it is to be familiar with even the most basic tenants of online security. Ever seen the folks who accidentally leave their personal Facebook pages open on the computers in Apple Stores? How about the people who desperately search for wireless networks in their immediate vicinity and automatically click on whichever ones doesn’t have a little lock requiring a password? Heck, I personally knew several people back in high school who would just mooch off of their neighbor’s unsecured Wi-Fi networks to connect their gaming consoles and laptops to the Internet.

Have you ever used a VPN? For many people, including some of the faculty and staff members at the University of Richmond, a VPN allows them to connect to programs that are normally only accessible via on-campus wired and wireless networks. They just flip a switch at the top of their screen, enter a password, and POOF! They now have access to the school’s servers. In fact, I used to use it to connect to Cascade, the University’s back-end server system, to publish my Spider Diaries blog posts for the Admissions Office without needing to be on campus to do it.

However, the most important feature of a VPN is its ability to encrypt the data that is transmitted between the client and the resources they’re trying to access. People can no longer eavesdrop on your connection, and it is extremely hard for personal information to leak during the exchange. I currently use a VPN 24/7 on my laptop, phone, and tablet via Private Internet Access (I promise, this is not an advertisement), and it has given me a much better sense of my own personal security as I go about my daily tasks. If you go to their website and click on the link at the top that says “My IP,” it will display the public information that is accessible via your IP address at this very moment. The VPN effectively scrambles this information and grants the user almost complete anonymity.

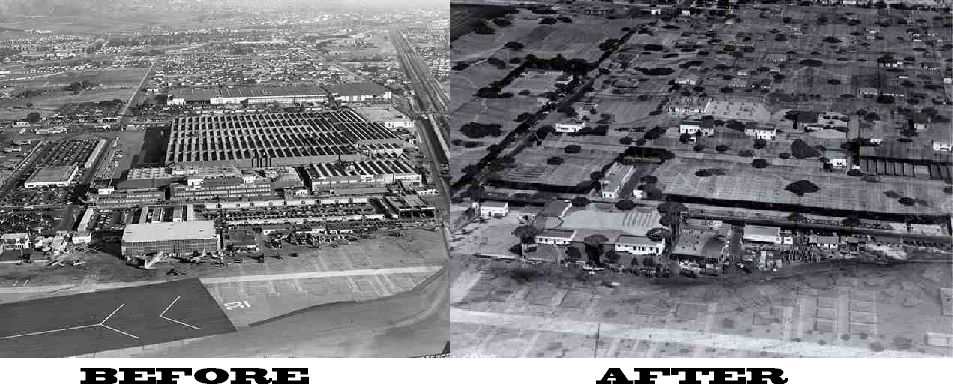

I’m a history buff, so I’ll use a historical example to describe this process. During World War II, companies like Lockheed and Boeing had huge manufacturing facilities that allowed them to construct bombers and transport planes for the U.S. Army Air Forces (USAAF). However, they needed to conceal these large-scale operations from the air in order to prevent any enemy scout or surveillance aircraft from seeing what they were up to. According to Boeing, “burlap houses and chicken-wire lawns camouflaged the rooftops of Boeing Plant 2 in Seattle so that, from the air, the bomber manufacturing center looked like a quiet suburb.”

Think of your connection and your device as the factory, physically planted in a valley or plain somewhere (or in your case, a home, a Starbucks, or a bathroom for those who like to play Candy Crush while doing their “business”). The snoopers, websites, trackers, spammers, criminals, and all-around mean people are the air surveillance folks that are actively trying to see what you’re up to. The tarps, burlap houses, and chicken-wire lawns are, in this case, the tools that the VPN uses to protect your online identity. Sure, the factory is still there pumping out airplanes, but all the enemy sees is a cute little suburb in the middle of nowhere. A suburb that has B-17s flying out of personal garages like magic.

See, people need to understand that online security doesn’t need to be about hiding the things you do. Instead, think of it as a necessary process to safeguarding the things you do do from being exploited by others. Just because I live in a safe neighborhood doesn’t mean that I leave my front door unlocked when I go to the grocery store. Just because I have trustworthy friends doesn’t mean I leave my social media accounts open when I’m away (because we all have that one friend who will type “poop” as your status).

Mr. Cameron can go on and on about the need to develop tighter security methods to protect against potential threats, but in terms of trying to loosen encryption standards, he needs to sit down and do a bit of research. Heck, I’ll help him out. In a recent article in The Guardian, Paul Bernal writes that “it’s hard to think of any serious part of the IT industry that doesn’t use encryption in a significant way – because encryption is critical to security, and security is critical to almost everything.” The reason why encryption techniques exist in the first place is to protect people like you and me from the same people that Mr. Cameron happens to feel threatened by, which adds an extra level to absurdity to his rhetorical question: “Are we going to allow a means of communications which it simply isn’t possible to read?”

Yes, Mr. Cameron. Yes we are.

It may be the case that his assertions were never intended to be taken literally. Maybe he was just trying to call attention to the difficulty of trying to decrypt potential threats. But the fact of the matter is that his stance is one that reveals a major disconnect between the way he thinks things should be and the way things need to be.

Regardless, David Cameron is almost certainly going to hear at least some of the arguments from critics in the coming weeks, so hopefully some of that will sink in. In the meantime, we can look forward to fighting whatever will be the next threat to our rights and privacy. I wonder what that headline will be…

Three…

Two…

One…

Wait, wait, looks like we have something!

9:39 am EST, January 20, 2015. “New police radars can ‘see’ inside homes.”

Man, why can’t I just sit in my apartment and browse Reddit in peace?