In Gazing (2019) Zhongkai Li explores voyeurism and authority. Li confronts the viewer with their own image projected upon a simple black screen; at once, the interpreted becomes interactive. With a user’s enabled webcam, Li plants their face into a revolving video channel with five other strangers. By moving the viewer from the schema into this uncomplicated space, Li allows them to arrive alone at the ideas introduced in his schema. His message: power resides in the gaze.

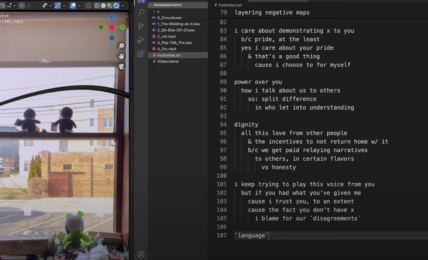

A schema lays the framework for Li’s art. In sketches, short phrases and quotes, he introduces his scopic field and theories of the gaze. The schema seems both a blueprint and a diary, introducing complex themes of surveillance while sharing personal theories on surveillance, power, and identity. In Li’s schema, a border of prominent philosophers accompanies his sketches and reflections on the gaze. Among other prominent theorists, Li names Michael Foucault and Laura Mulvey. Foucault’s panopticon and Mulvey’s male gaze theory seem to have had a significant effect on Li’s Gazing. Each uncovers the divergent ways the gaze can strip power.

In Foucault’s panopticon, the gaze rests its authority in surveillance. Foucault expands philosopher Jeremy Bentham’s original theory to use the panopticon as a method to describe society’s oppression of the individual. The famous theory describes a watchtower in the middle of a circle of prisoners’ cells. In their cells, prisoners can only be sure of two things: the unwavering presence of the watchman, and the possibility that the watchman could be turned toward another cell. These two certainties create a power that is both visible and unverifiable. As a function in society, these two facets of the panopticon gaze create unfettered authority.

These two aspects of power are identifiable in Li’s five-way video. The camera’s gaze on the viewer is visible. As a viewer clicks the link, their face becomes an object on the screen, their webcam light turns green, and every movement is live. Li ensures that viewers are aware they are being observed.

The camera’s gaze on the viewer is unverifiable. The viewer is unaware of the other four viewers’ true existence — whether they are able to observe, or if they are pre-recorded subjects. The viewer is able to watch as the other four participants look down at their screen, staring at them. Every few minutes, the other participants turn off their cameras, another taking their place. Li creates uncertainty; although a viewers’ camera is on, it is difficult to tell whether the camera projects their image onto another viewers’ screen.

Li makes the viewer feel aware yet unsure. As a result, the gaze of the camera limits them, reducing their power over their actions in fear that someone else might be viewing them, in turn.

Feminist film theory supports this view of the gaze as power-inducing. Laura Mulvey, feminist film theorist, forwards a male gaze theory which describes how the gaze harbors power by defining its subject. Mulvey’s theory, a response to pervasive objectification of women in modern entertainment, illustrates how films are written from the point of view of a heterosexual man. This restricts viewers to watch films only from the point of view of a heterosexual man, reinforcing disparaging depictions of women. By viewing women in film in a certain way, men define and perpetuate their own categorizations of them. As a result, the gazer gains power as it defines its subject. By placing the viewer into his own work of art, Li depicts this phenomenon of the gaze. When the web camera turns on and the viewer becomes the subject of his piece, they lose power over their own portrayal. They are voiceless and unable to move their own image on the screen. Li limits a viewer to be a mere subject of the camera’s gaze in his piece of art, exerting power in the process.

Li brings pure theory into practice as he moves the panopticon and male gaze theory into interactive video. In doing so, Li makes the viewer question the ways we are confronted by society’s normalizing gaze in everyday life.

Check out Zhongkai Li’s Gazing

:::

Head Editor Alexis Angelus is a senior studying Journalism and Politics/Philosophy/Economics/Law at the University of Richmond. When she’s not working as a marketing associate in the A&S Communications Department and managing social media for the school newspaper, Alexis enjoys photography and playing with PhotoShop and Illustrator.

HMU | Marina Tinone →